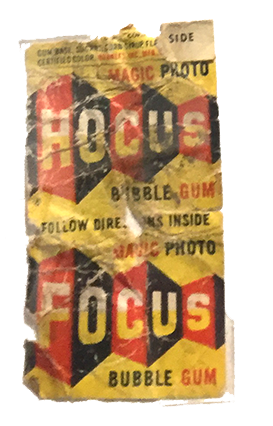

World War II Posters

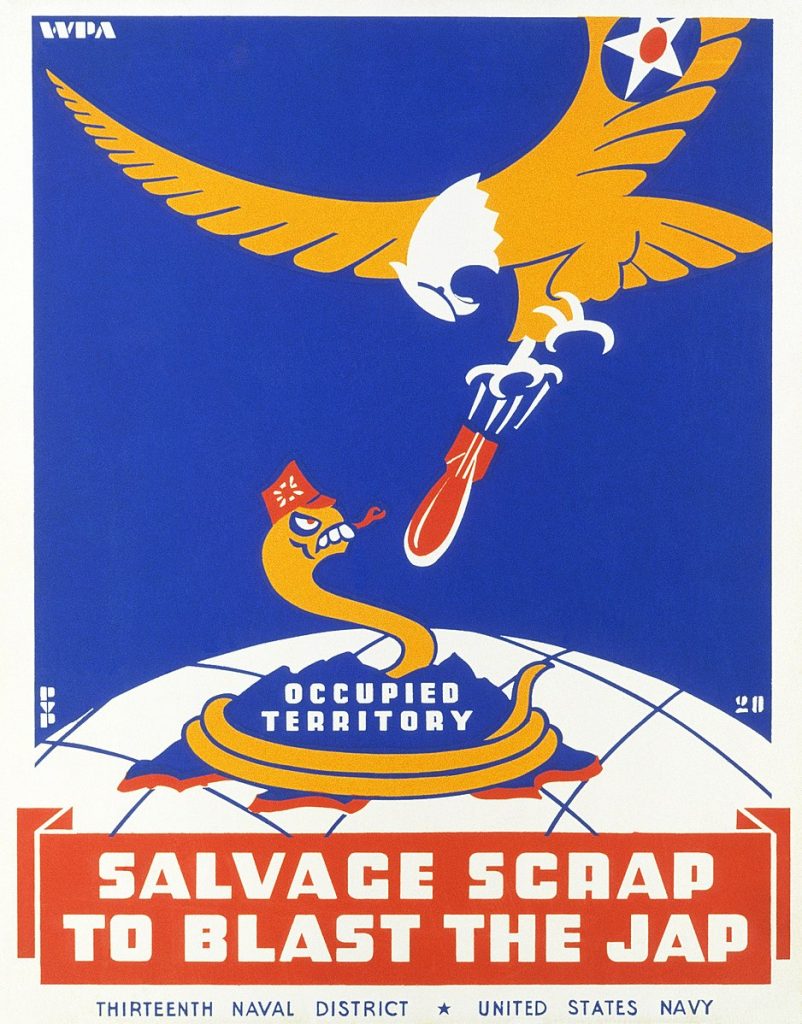

The propaganda for reuse in World War II emerged in many forms, including racist posters: "Salvage Scrap to Blast the Jap!" and "Slap the Japs with the Scrap!"1

During the war, materials had to be further sorted, defined, and collected in order to be used the war efforts. However, the collections were expensive, and occasionally the government used more money in collecting the material than using it.2

Source: Phil von Phul. "Salvage scrap to blast the jap." Federal Art Project (Washington: WPA Art Project). Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington D.C.

Rubber

As shown in this picture, the streets literally had dirt on them - dirt that needed to be cleaned up.

The edges of the streets also often had abandoned automobiles on them. The Department of Sanitation was authorized to collect these abandoned vehicles in the 1940s, a job that had originally needed police presence. 3 William J. Powell. "Functions and Procedures of the Department of Sanitation." January 20, 1944. NYC Municipal Archives Library, New York City.[/FOOTNOTE] Thousands of vehicles were simply left on the side of the streets each year, which caused not only traffic but delays of services such as garbage pick-up or street sweeping.

The government took an interest in such abandoned automobiles during the War, as they provided salvage material to help with wartime efforts.

Source: Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. "West 71st Street - Broadway" New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Peanuts

Peanuts were a popular street vendor food in the 1930s.

The many street vendors sold nuts that had shell inevitably fall on the streets.

See other photographs of a nut vendors.

Source: Fred Palumbo, photographer. Man selling nuts from his pushcart, New York City.

World Telegram & Sun photo by Fred Palumbo. New York, 1947. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress,

Dixie Cups

The Dixie Cup Company began to make more than just disposable paper cups after the World War. Dixie Cups and the Company grew wildly successful, and the growth of the company made sure that disposable products became an essential and convenient part of everyday life.

Paper was the most common material thrown away in litter baskets. Though paper could be recycled, clearly it was not kept.

Source: Dixie Cup, 1940s. Whistlin' Dixie: Marketing the Paper Cup, Skillman College. Digital Exhibition.

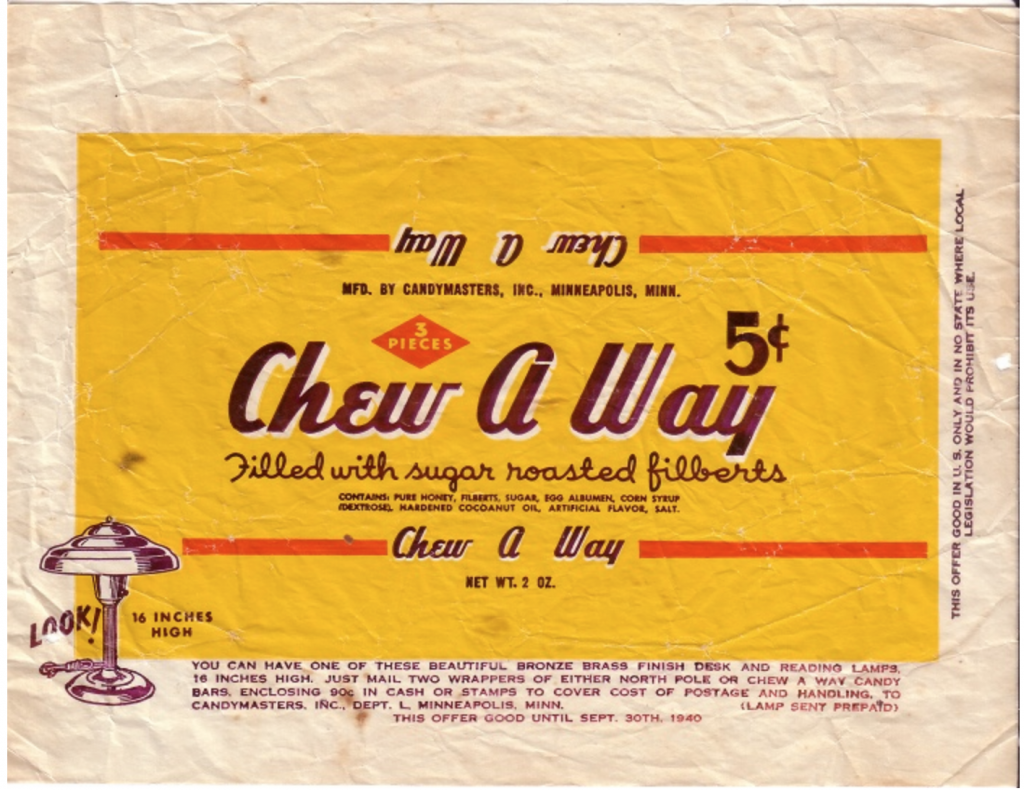

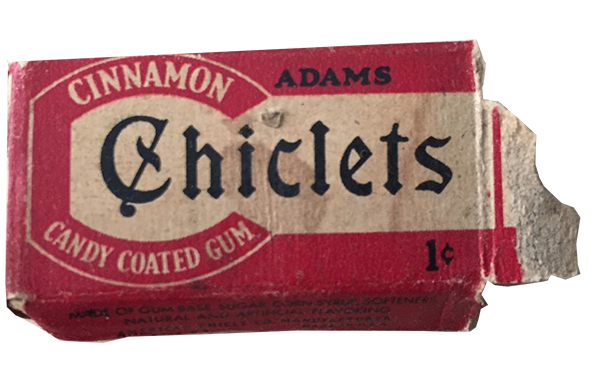

Chiclets

Source: Chiclets, circa 1940s. Closet Archaeology.

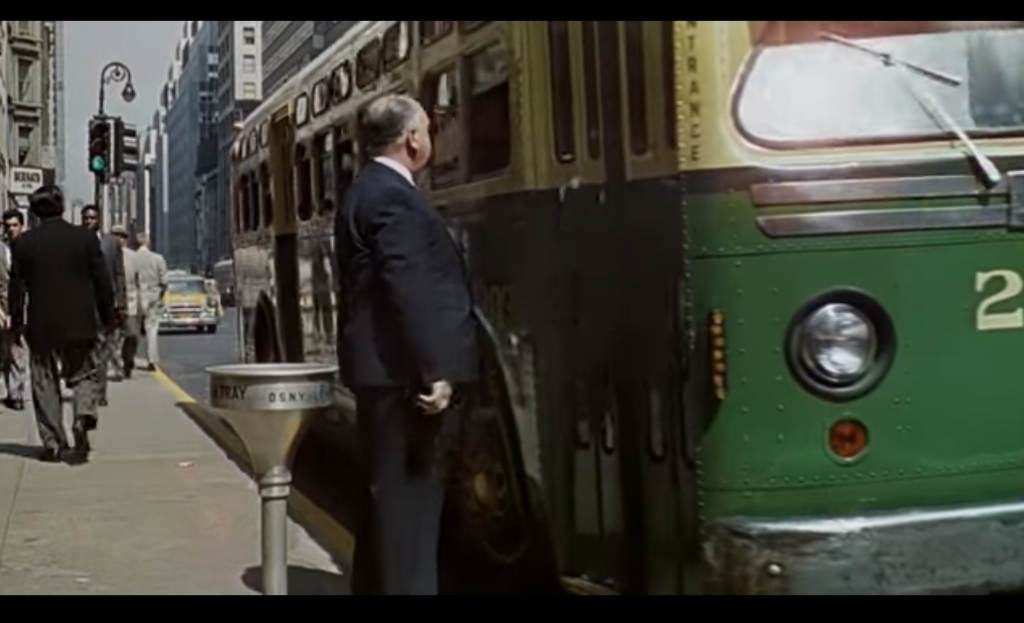

North by Northwest

Many movies shot in New York City show the streets and the sanitation facilities on them.

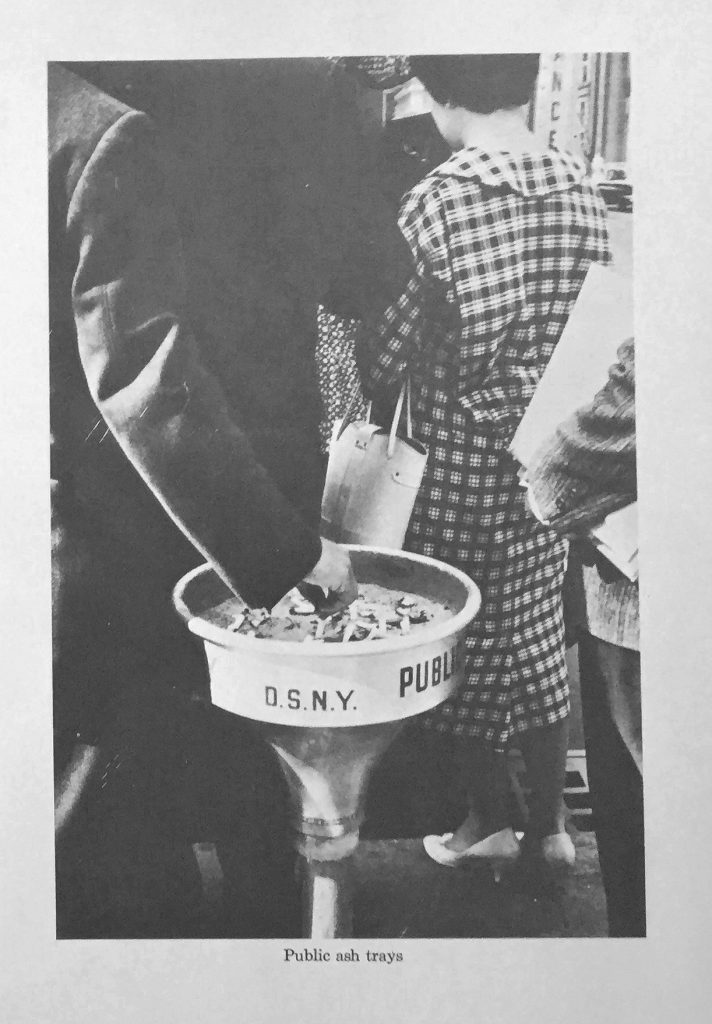

North by Northwest shows the public ash trays set out by DSNY in the 1940s and 1950s to collect ash.

Find the lucky cigarettes package on this page for a closer look at the ash trays.

See the famous opening credits here.

Source: Alfred Hitchcock, dir. North by Northwest. Hollywood:: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. 1959. Film. Cary Grant.

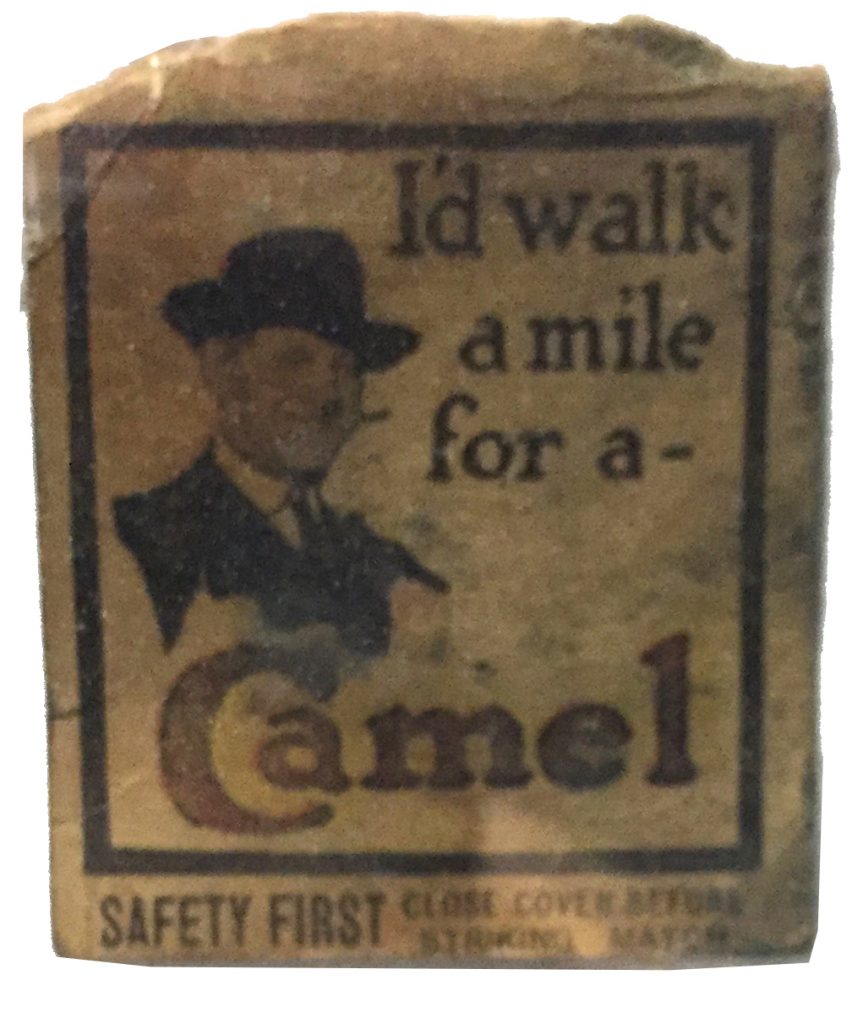

Camel Matchbook

Cigarette consumption doubled during World War II with an increase in women smokers, armed forces, and teenaged customers.4After the war, tobacco companies continued successfully to marked a variety of products, including the "filtered cigarette." Additionally, the popularity of a soft paper cigarette packaging (a flip top box) rather than metal and matchbooks, added to the litter on the streets.

Source: Camel Matchbook, 1940s. Closet Archaeology.

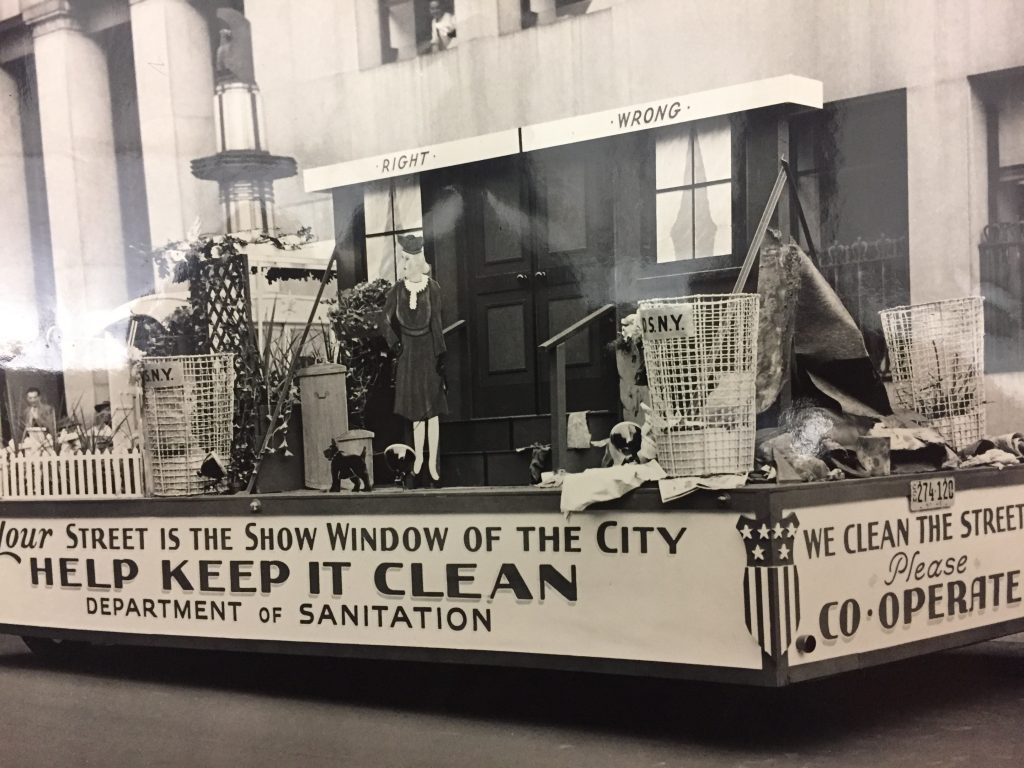

Floats

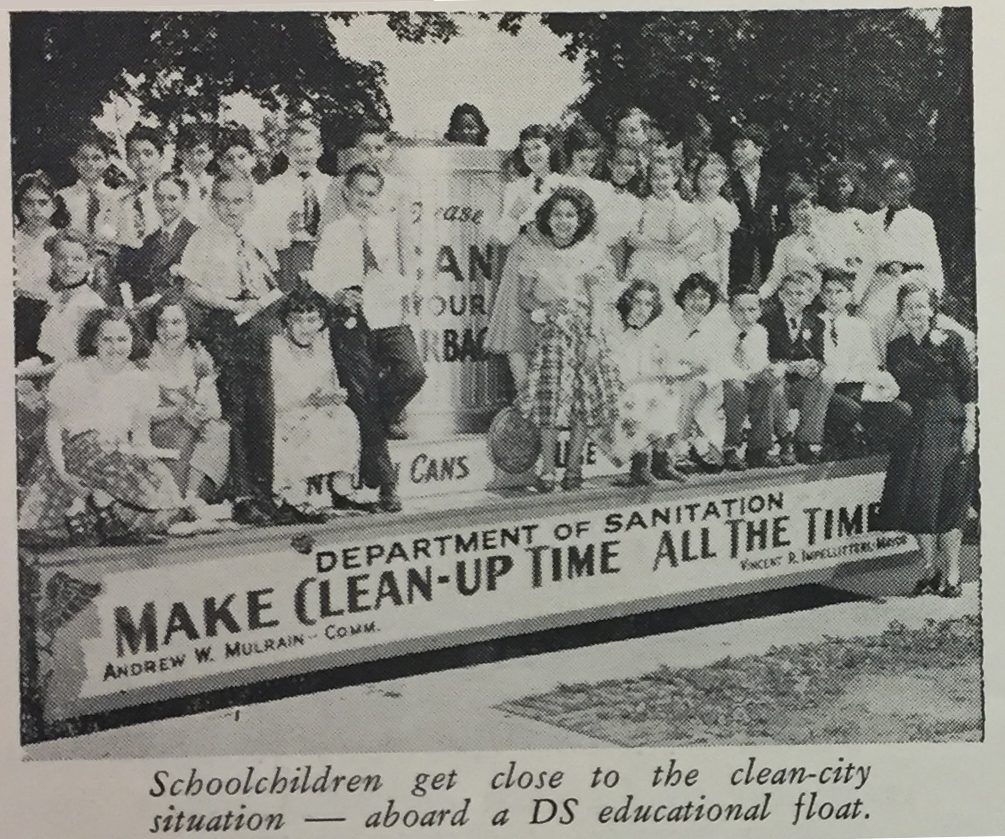

Floats designed by the Department of Sanitation's Public Relations department became a spectacle. This float in particular showed the specific items that were modeled to be put into a litter basket. Such floats often were accompanied by a parade with the Department of Sanitation Band, from City Hall to the Sanitation Department headquarters, 125 Worth Street.5

In trying to eliminate litter, the things unwanted became more visible than ever.

Source: Photograph of Float, 1940s. Box 8, Outdoor Cleanliness Association archives, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Closed Top Baskets

552 swing-top "paper and rubbish" cans were purchased in 1934, empty of any advertising. These had already been distinguished as for paper or rubbish, and used various closed tops. Closed tops stopped any weather elements from soaking the baskets and unsightly smells and sights were covered.

In 1949, 736 litter baskets (each valued at $10) were stolen. Labeling the baskets with Department of Sanitation became crucial.6However, the actual lettering of the baskets was kept fairly simple, aiming for a "pleasing appearance to gain maximum public acceptance." 7 The baskets alone often weighed over fifty pounds - with their “light refuse,” even more.

The lidded receptacles are shown in The Lost Weekend, when the protagonist, Don Birnam, wanders the streets of New York City.

Source: Wilder, Billy, dir. The Lost Weekend, 1945; Universal Pictures, 2001. DVD.

Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. "715 Fifth Avenue - East 56th Street" New York Public Library Digital Collections.

The trash can image was reimagined by jaime ding.

Coca Cola Bottle

This bottle is an example of glass materials that would have been seen on the streets.8The green glass, called "Georgia-green," was chosen in the 1910s over ambers and blues, becoming an iconic color for Coca-Cola bottles and hence, an iconic color in litter baskets.

Source: Coca-Cola Bottle, circa 1940. Private Collection of jaime ding.

Paper Products

The Dixie Cup Company began to make more than just disposable paper cups after the World War. The growth of the company during the war made sure that disposable products became an essential and convenient part of everyday life.

Paper products continued to be the most common material thrown away in litter baskets. Though paper could be recycled, clearly it was not kept, and not meant to be valued.

Source: Clark Gable Ice Cream Lid, 1940s. Whistlin' Dixie: Marketing the Paper Cup, Skillman College

Paper Products

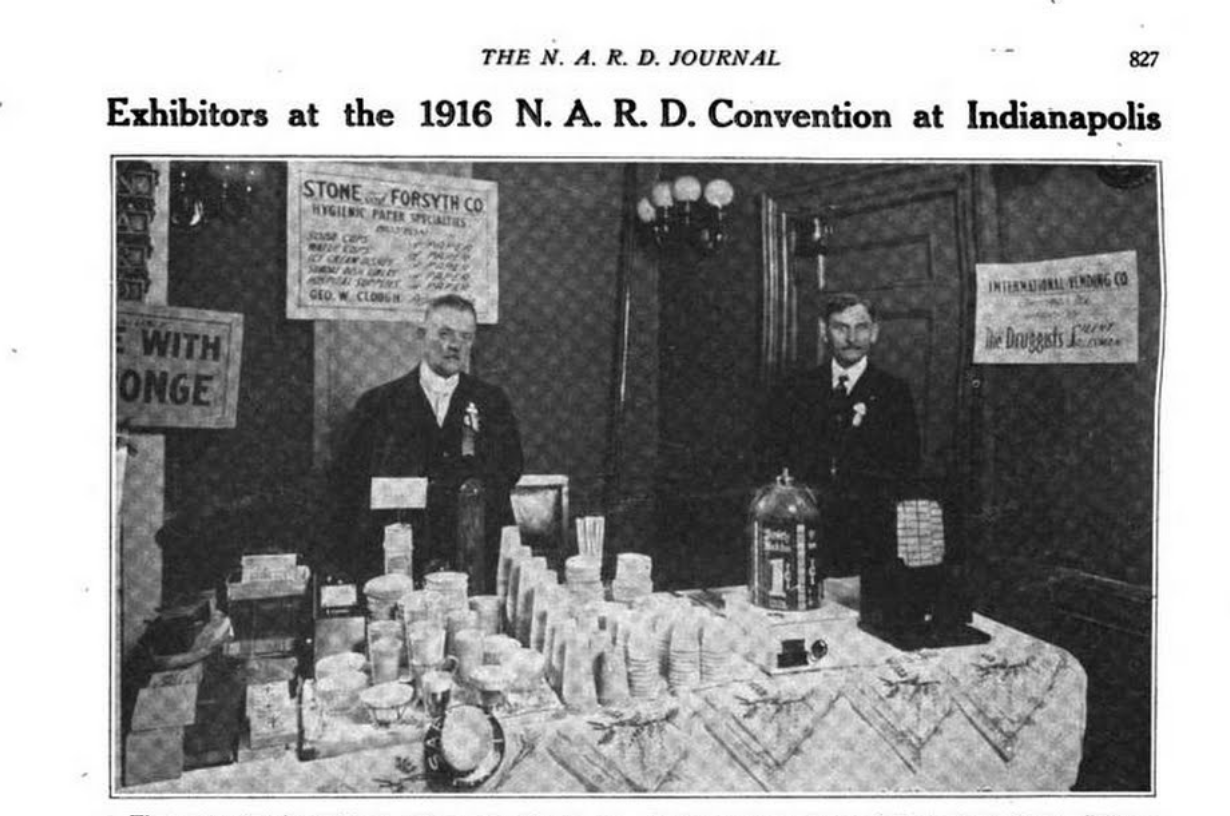

Disposable paper products in education had been used since the beginning of the 20th century for sanitary reasons.9 These bottle cap covers were used to designate exactly that - the sanitary authorization of New York City School Programs.

Paper products continued to be the most common material thrown away in litter baskets. Though paper could be recycled, clearly it was not kept, and not meant to be valued.

Source: National Association of Retail Druggists Journal.

Milk Lid, 1940s. Closet Archaeology.

"Fruit Peelings"

"Fruit peelings" was determined to be a type of "light litter" by the Citizens Committee to Keep New York Clean.

But which fruits? The range of fruits available in New York City grew during with the rise of imports and advances of refrigeration in the 20th century.10

While bananas became available and cheap by the end of the 1940s, apples had always been a major food group, available through street peddlers, fruit stands, and open-air markets.11 Fruit peelings also looked different throughout the island, as neighborhoods became ethnically centered and food ways adapted for each specific neighborhood.

Source: Evans, Walker, photographer. Untitled photo, possibly related to: New York. New York, 61st Street between 1st and 3rd Avenues. A fruit and vegetable vendor stand. New York New York State United States, 1938. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017732877/.

MAKE CLEAN-UP TIME ALL THE TIME

The Department of Sanitation's litter baskets were the central item in many parades and events. The Junior Inspector's Club hosted many parties, a chance for the celebration of the students' efforts in cleanliness and for manufacturers and businesses to sell products. Celebrations were not only attended by the Commissioner of Sanitation, radio stars, and actors, but also sponsored by the Sunshine Biscuit Company, and Sheffield Farms.12

Other events included using young people and demonstrating how to clean the streets, such as this photograph, titled "Group of Harlem youths recruited as street sweepers."

Source: Department of Sanitation, City of New York. Annual Report, 1952. Outdoor Cleanliness Association records, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. "Group of Harlem youths recruited as street sweepers on 117th Street, ca. 1940s" New York Public Library Digital Collections.

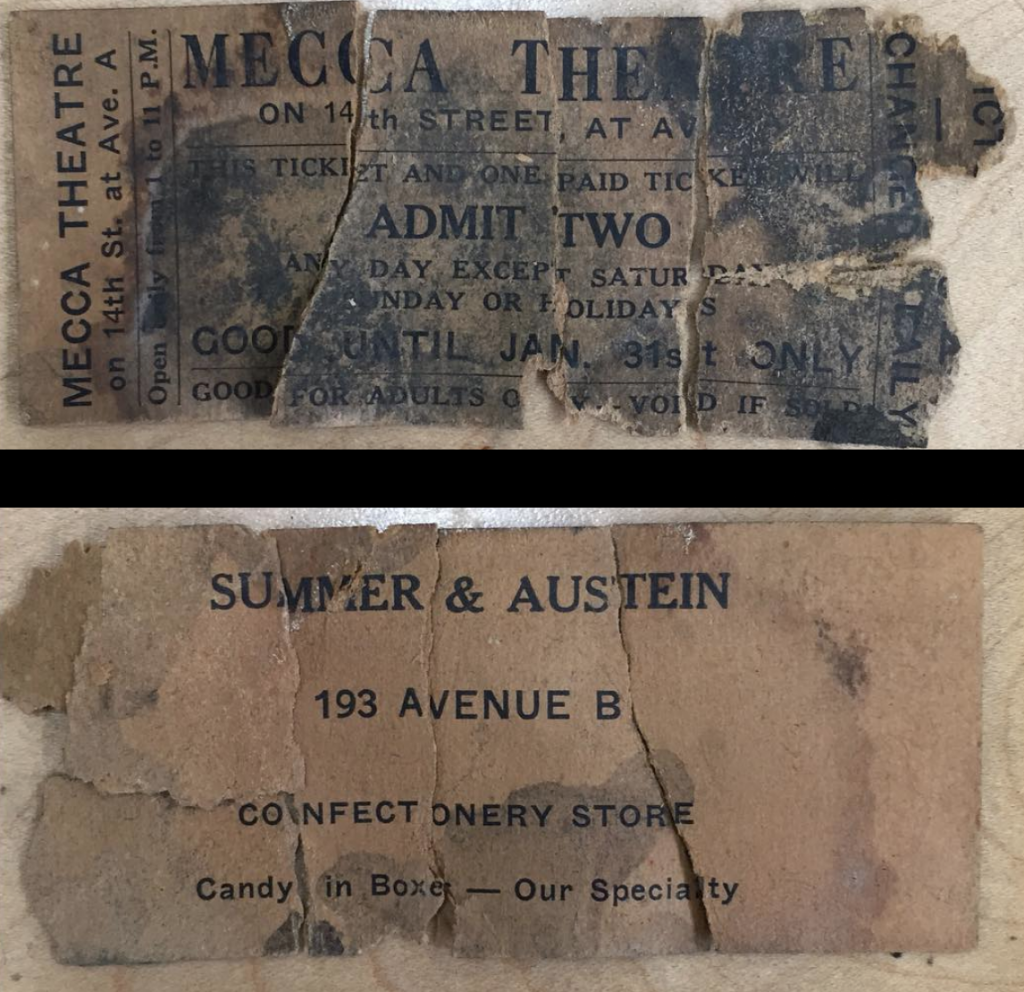

Cigarette Packets

The many ashes and matches littered on the streets and sidewalks called for innovations to collect them, like this public ash tray. These "new facilities" were more ways to sort and contain unwanted substances. Often placed by bus stops and on street corners, the public ash trays both marked and designated public spaces.

Cigarette consumption doubled during World War II with an increase in women smokers, armed forces, and teenaged customers.13After the war, tobacco companies continued successfully to marked a variety of products, including the "filtered cigarette." Additionally, the popularity of a soft paper cigarette packaging (a flip top box) rather than metal, added to the litter on the streets.

Source: CLEAN CITY, USA: A Record of the Activities of Young & Rubicam as Volunteer Advertising Agency for Citizens Committee to Keep New York City Clean, Inc., May 1955-July 1959.

Lucky Strike Cigarette Packaging, 1940s. Flicker Advertisement. Web.

While “trash,” “litter,” and “waste” may seem interchangeable, each term indicated different methods in managing the world of the unwanted.

The different definitions that these terms refer to a wide range of materials that were left on the streets of New York City, and revisiting what exactly was unwanted gives a glimpse of the city in the 1940s. “Waste” included a lot of material that no longer on the streets today, such as dead animals, dirt, or cinders from power plants. Officially, “trash” was a colloquial term, while “refuse” named what the Department of Sanitation had to worry about. Within “refuse,” “garbage” and “rubbish” further delineated the wetness of the material, crucial in collection and disposal.

As more people gathered in New York City and had more things to dispose, governments began to undertake seriously the responsibility to implement the best methods for getting rid of waste.14After the federal government banned dumping waste in the ocean in the 1930s, New York City built more municipal incinerators and sewage plants in Queens, the Bronx, and Brooklyn.15The municipal government also began negotiating with private cartmen, who had always profited from removing wanted materials, to develop a permit system. This drew boundaries between private and public services and private and public waste.16 Private waste from residents needed to be in covered metal cans, a physically different container from the litter baskets that were for “public” waste. By 1949, over 8,000 litter baskets could hold “public trash,” trash created and disposed in public places.

While trash was formally defined by the municipal government in order to be collected, it was unofficially defined by who and where they created it. Those who with more financial resources and more material wealth often produced more trash than those who had less, but the wealthy’s ability to place items in the “right” place made them believe themselves to be much cleaner – both morally and physically – than those who had different systems. To those who considered themselves “clean,” dirty neighborhoods directly correlated with the “reputation of the people,” even though dirtiness was often exaggerated or assumed, like in this WNYC radio clip.

During World War II, many materials were collected for the war effort. Similar to Sanitation Education strategies, wartime propaganda appeared in many forms, including posters and radio ads, and encouraged patriotic citizens donate anything they had to spare: old rubber tires, second tin pots, or bits of fat leftover from cooking meals.17The Office of War Information and the Bureau of Motion Pictures produced TV segments as well (what you are hearing now), directing people on how to be the best patriots during the war. The language used in these materials emphasized them as “scrap” materials, carefully marking the “common things we throw away” as scrap rather garbage or even trash. These materials were items to be “salvaged,” a heroic action, rather than sorted into correct containers.

♬ Salvage, The Office of War Information and Bureau of Motion Pictures, 1943.

Also see recommendations for nutritional practices.

Learn trash talk from the flip cards below.

Many of these definitions are from the 1941 American Public Works Association Refuse Collection Practice, a culmination of five years worth of government-sponsored collection practice studies from across the country. The definitions stayed largely static for the next forty years.18 Other definitions are from private associations who did not need to consider the methods involved in collecting, but still used terms to teach what trash went where.

Ashes

Ashes

Incinerators were commonly used in both business practices and in homes; ashes were seen as valuable fertilizer. DSNY used large scale incinerators from 1934-1999.

Dirt

Dirt

The APWA categorized dirt under “street refuse,” along with street sweepings, leaves, catch basin dirt, and contents of litter receptacles.Garbage

Garbage

The APWA: “Animal and vegetable waste resulting from the handling, preparation, cooking, and consumption of foods….decomposes rapidly, particularly in warm weather, and may soon produce disagreeable orders. When carelessly stored, it is a source of food for rats and other vermin, and serves as a breeding place for flies. Includes market refuse.”

Litter

Litter

The APWA: “small items of disposal while walking, see Paper, Dirt, Salvage Material.” The CCKNYCC used vague graphs and charts to describe litter, separating the category into Heavy Litter (dog nuisances, junk, garbage, grime, peelings) and Light Litter (cigarette, candy wrapper, scrap paper, newspapers).

Offal

Offal

The APWA: “This class of refuse has a rather high value because of the grease and tankage that can be produced from it in rendering plants. … Animals are particularly offensive from both sanitary and aesthetic viewpoints and usually must be collected promptly.” DSNY reported not only cats and dogs, but also horses, cows, and, in 1935, 1901 pounds of dead monkey.20

Paper

Paper

Paper was most frequently cited and seen material thrown away. With 10 major dailies newsprint often crowded litter baskets, such information was clearly easily disposable even though paper could be recycled.

Public

Public

Are you a resident of New York City?

Are you using a litter basket of New York City?

Do you walk on the streets of New York City?

Do you read English?

Do you speak English?

Are you in public school?

Refuse

Refuse

The APWA: “Solid wastes. In connection with some problems, its point of origin is important: domestic, institutional, commercial, industrial, or street refuse. For other problems the point of origin is not so important as the nature of the material itself.” Includes Garbage, Rubbish, Ashes, Dead Animals, Automobiles.

Rubbish

Rubbish

The APWA: “All refuse not included in garbage and ashes. A mixture of ‘combustible rubbish’ and ‘noncombustible rubbish.’ Includes paper cartons, wood furniture, metals, tin cans, dirt, glass, mineral refuse.” In the 1966 edition, APWA added leather and rubber into the ‘combustible’ category.

Salvage Materials

Salvage Materials

Materials, such as cooking fats, rubber tires, tin pots, and paper, collected to donate to War efforts during World War II.

Snow

Snow

Though perhaps not usually considered waste, snow was the responsibility of the Department of Sanitation, whose vehicles had to not only be strong enough to collect trash and snow. The Department began implementing emergency laborer snow removal procedures rather than using private contractors in 1934.21

Trash

Trash

The APWA: A colloquial term, sometimes “miscellaneous household debris other than garbage and ashes…or …yard debris.” in 1957, The NY Herald Tribune claimed 5 million tons of trash was being picked up each year.22 Private organizations rarely used the word trash.

Waste

Waste

The APWA: “the useless, unused, unwanted, or discarded materials resulting from natural community activities. Includes solids, liquids, and gases.”