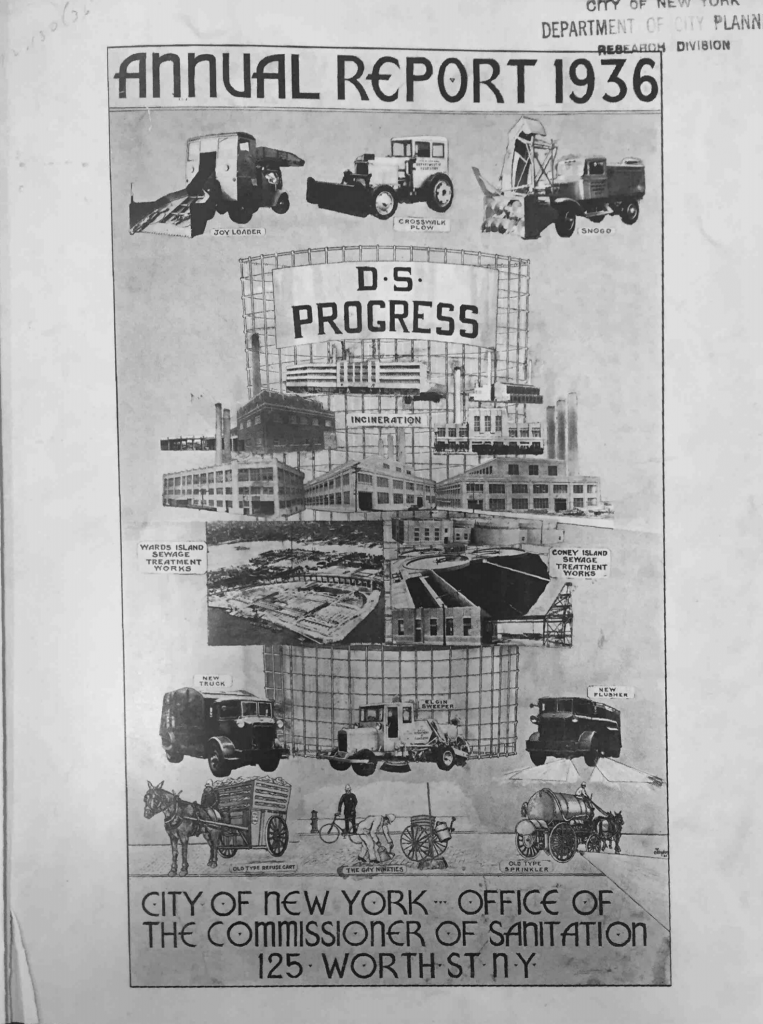

Department of Sanitation Annual Report, 1936

The Annual Report of 1936 proudly displayed of all of the Department of Sanitation's technological accomplishments. The contents included methods of collection, personnel changes, statistics, budgets, and much more:

"The Department has purchased additional wire baskets and we now have on the streets approximately 7040. They are practical and are educating to the general public, who are gradually becoming 'litter conscious.' "2

Source: Annual Report 1936. Department of Sanitation, City of New York. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archives Library.

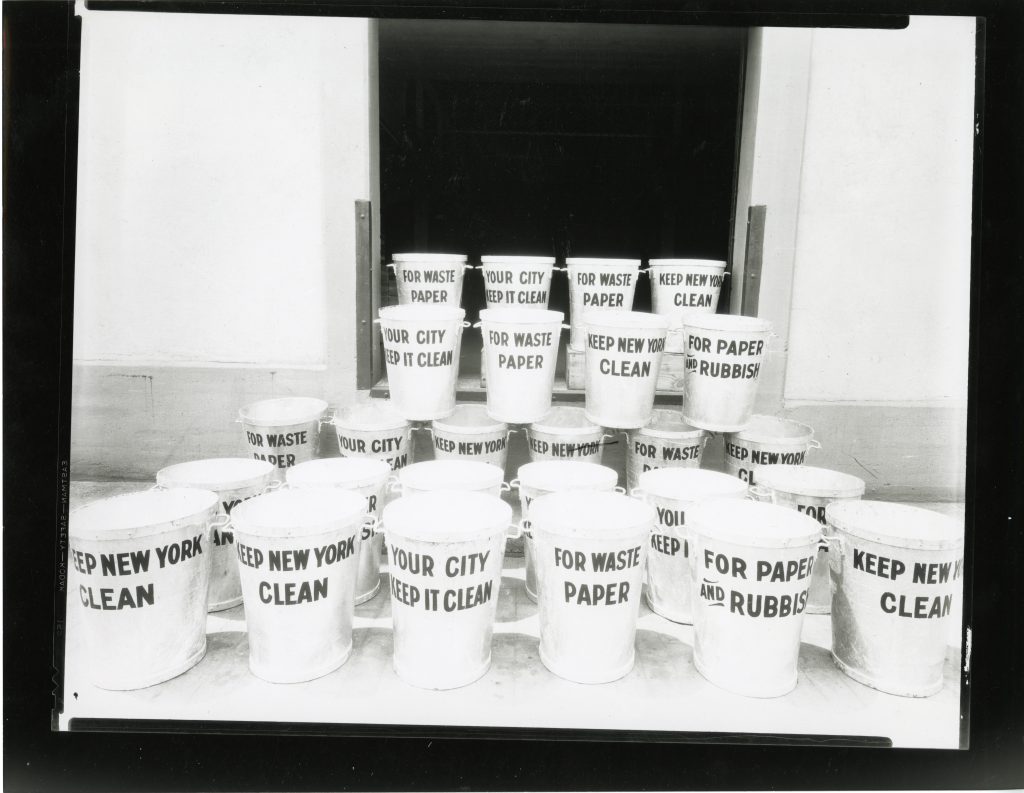

Litter Cans, 1936

Design of the litter baskets had yet to be formalized before 1934. Once they were, the Department of Sanitation maintained that they should not be covered in distracting advertising, but directly state the materials they were supposed to contain, sorting material (paper and fruit skins, for example) for collection.

The official, standardized litter baskets were all painted white, and only used English labels.

Source: 1936 Trash Cans, Department of Sanitation, City of New York. NYU Faculty Digital Archive.

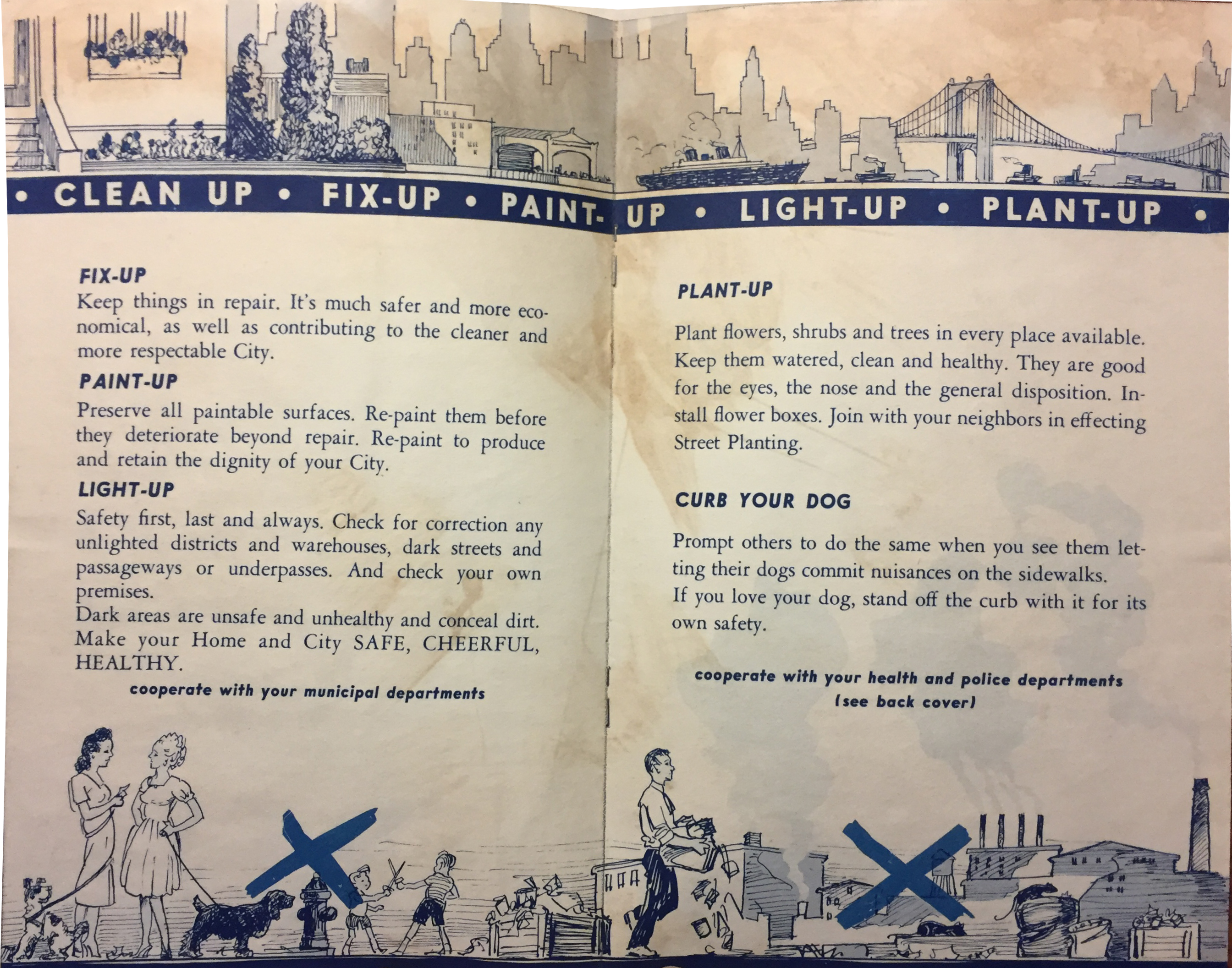

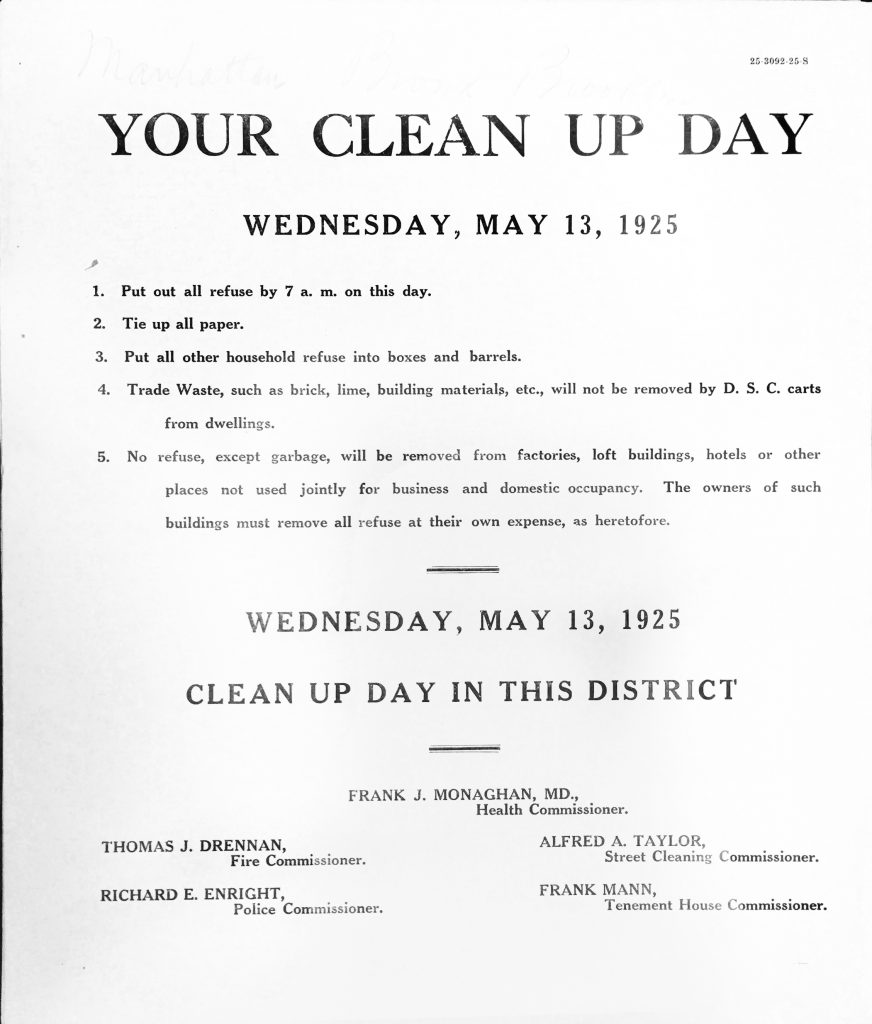

YOUR CLEAN UP DAY

Even before the creation of the Department of Sanitation was formed, efforts to clean the city emerged from other municipal areas. The Department of Health and the Department of Parks often tried to push clean up initiatives, such as Clean Up Days. The city was divided into a total of 51 sections, and each section was to clean up on a specific day. These flyers were passed out, amounting to about 150,000 total flyers notifying residents to clean up their city.

Source: Clean Up Week (H34,32 LL) Department of Health, the City of New York. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archives Library.

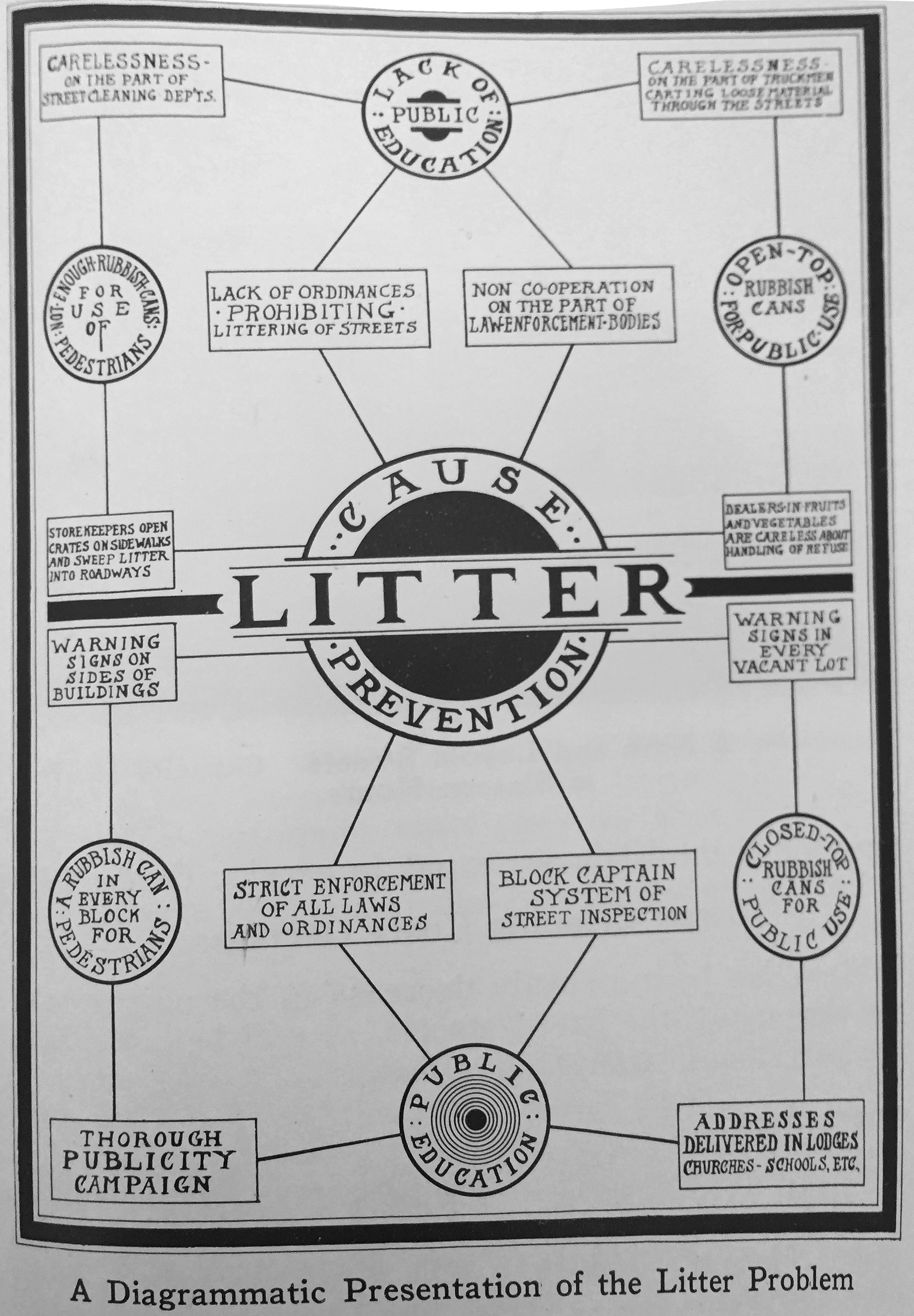

Municipal Sanitation

Published from 1930-1940, Municipal Sanitation: A Journal for the Practical Sanitary Official, began with posing a problem:

is sanitation a public or private responsibility?

Litter was specifically targeted as an important problem.

The following page from the magazine diagrams the issue:

Source: Municipal Sanitation. New York Public Library, Science Industry and Business Division.

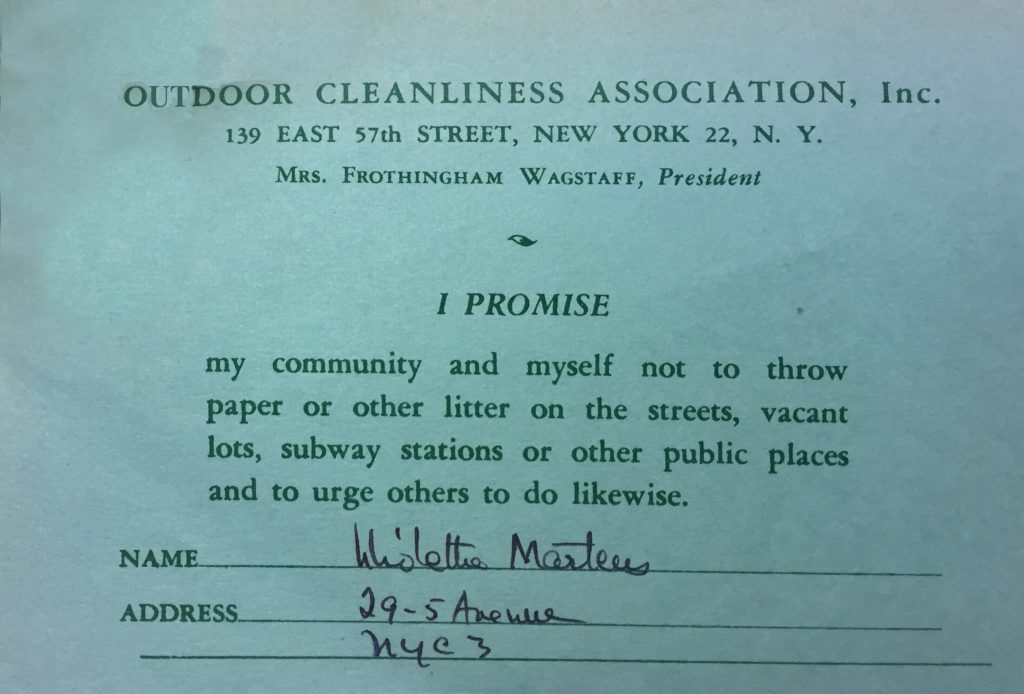

I Promise

While pledges were used throughout Sanitation Education, they were used for adults as well. The OCA educated adults when they had the chance with cards such as this one.

This distribution of cards was not a new strategy:

Outdoor Cleanliness Association Pamphlet

The Outdoor Cleanliness Association passed out to thousands of this pamphlet, "Civic Pride in Your Hometown," to thousands of school children over three decades. Principals would write to the OCA for one copy for each of their students.

Click on a page below to read the whole pamphlet.

Source: 1936 Pamphlet, Outdoor Cleanliness Association records, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

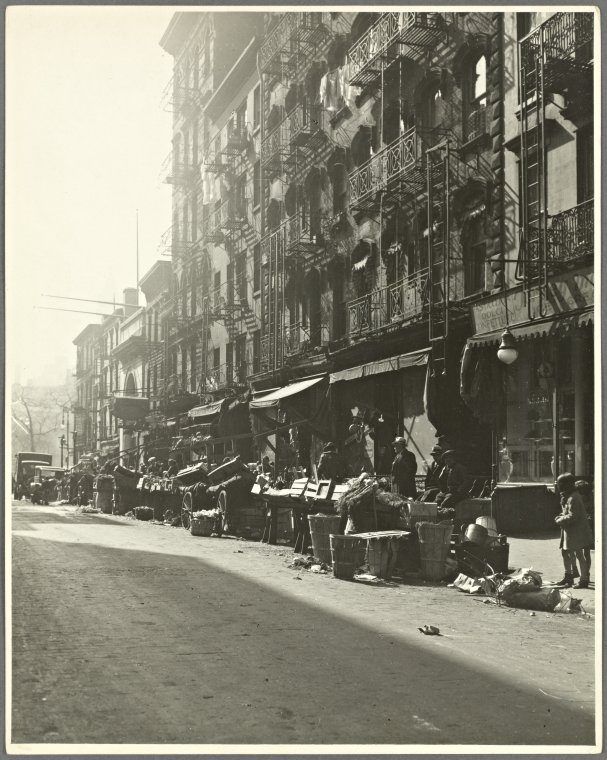

Fruit Peelings

New York City took on its nickname The Big Apple around the 1930s. Apples were quite common on the streets of the city, often sold as for 5 cents as a form of employment during the Great Depression.

Source: Hester Street, between Allen and Orchard Streets, Manhattan. 1938. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. "Hester Street, between Allen and Orchard Streets, Manhattan." New York Public Library Digital Collections.

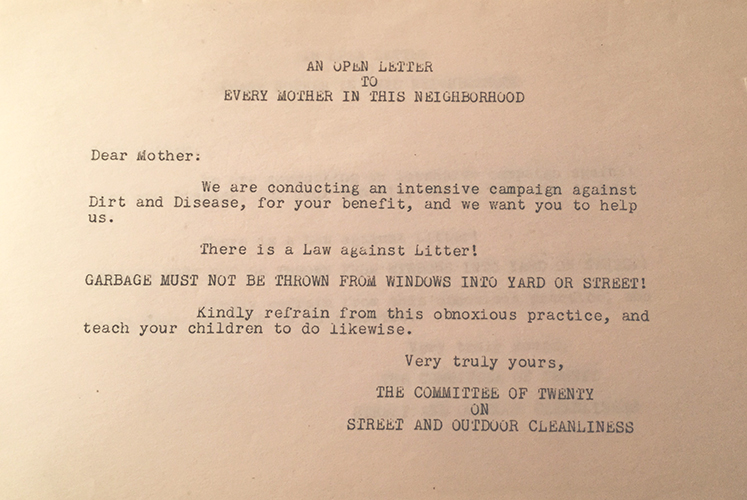

Pay Day: 1 Cent

Sanitation Education heavily targeted candy wrappers, using them frequently as examples of placing something where it is not supposed to go. The number of times candy wrappers were cited creates an image of the streets in the 1930s completely papered with them, though that generally was not the case.

Source: 1930s Payday, candywrapperarchive.com.

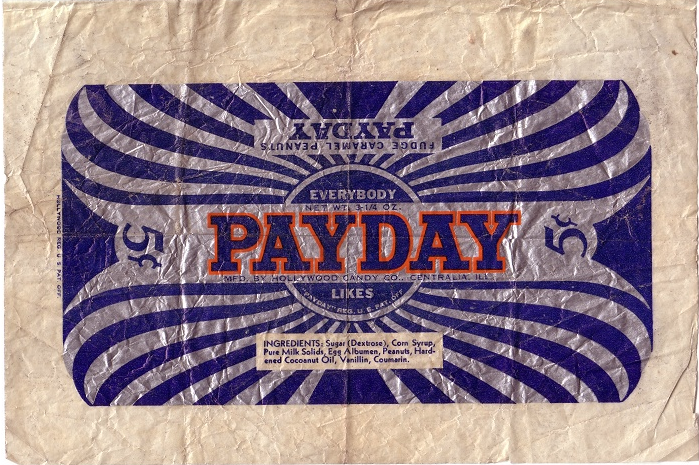

Contest for the Design of a Litter Basket

The New York Academy of Health's Committee of Twenty on Street and Outdoor Cleanliness sponsored a contest to design litter baskets that were "substantial, neat and attractive in appearance" for the newly formed Department of Sanitation. Click to open a PDF of the contest rules and requirements.

The winners, both submitted by art school students, resembled European designs. Indeed, the Committee of Twenty felt that European cities were the ideal model for creating a clean city.

Dr. George Soper, holding a PhD in sanitation engineering, was sent across seas by theCommittee of Twenty on Street and Outdoor Cleanliness to observe and report upon European practices to make NYC a “cleaner and far more attractive city.” Soper’s travels noted the types of street cleaning devices and methods, and were published in Street Cleaning and Refuse Collection and Disposal in European Cities with Suggestions Applicable to New York in 1929.

Source: "Contest for the Design of a Litter Basket." 1929. New York Academy of Medicine Archives.

"New York City Litter Basket Prize Awarded." Municipal Sanitation, November 1930. (New York: Case-Shepperd Mann Publishing Corporation), 644.

Barrels

Before the official installment of municipal litter baskets, old oil barrels and reinforced wooden barrels were used for collecting trash, especially in places that had more frequent activity, like open air markets.

Source: Wurst Brothers. "Elizabeth Street," circa 1930. Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. "Elizabeth Street" New York Public Library Digital Collections.

This litter basket was reimagined by Jaime Ding.

Clean City League Badge

This Clean City League Inspector badge is no bigger than a thumb. However, in the 1930s, it displayed immense power. Only the officers of the Clean City League (the President, Vice-President, Secretary and Treasurer, all were appointed by a teacher) were given gold badges. Other students could be Inspectors, who received silver badges. 3

The Department of Sanitation's Sanitation Education division provided these badges, along with pledges, pamphlets, and certificates. In its inaugural year, Mrs. Constance Warring visited 227 public schools and gave out 5,174 badges. 4

In 1937, over 200 Clean City Leagues were formed in schools in Brooklyn, Manhattan, the Bronx, and Queens.

Source: 1930s Clean City League badge. Private Collection of jaime ding.

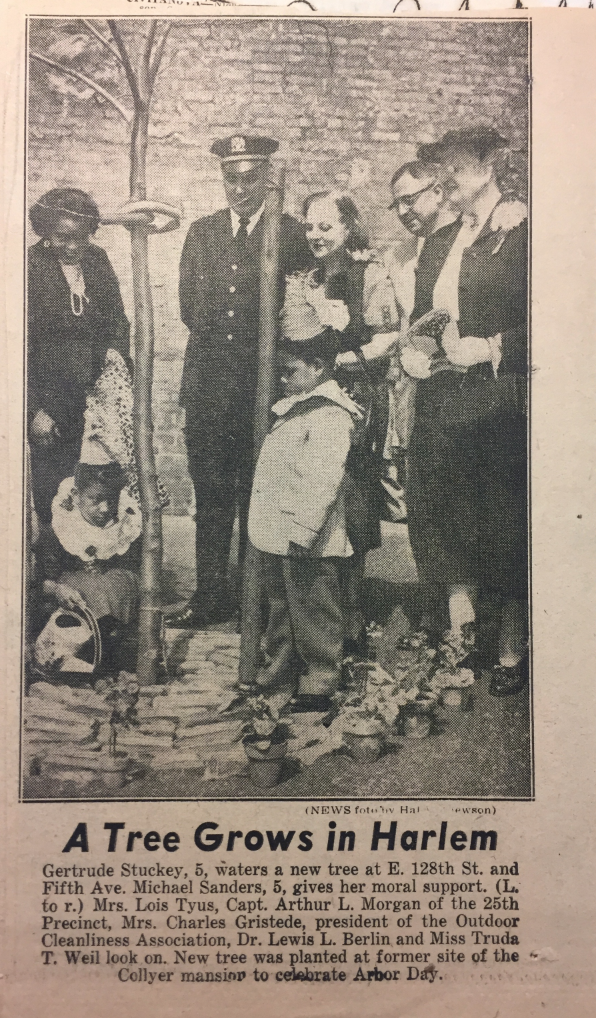

Harlem: A Success Story

In newspapers and radio spots more than other areas of Manhattan. Students in Harlem could be cited as "shining examples" and a model of "successful" sanitation education. This pattern continued throughout the next few decades in coverage about sanitation education.

Source: Newspaper Clipping, Outdoor Cleanliness Association archives, Manuscript and Archive Division, The New York Public Library.

Treasure Gum

Sanitation Education heavily targeted candy wrappers, frequently using them as examples of placing something where it is not supposed to go. The number of times candy wrappers were cited creates an image of the streets in the 1930s completely papered with them, though that generally was not the case.

Source: Treasure Hunt Gum, 1920s. Closet Archaeology

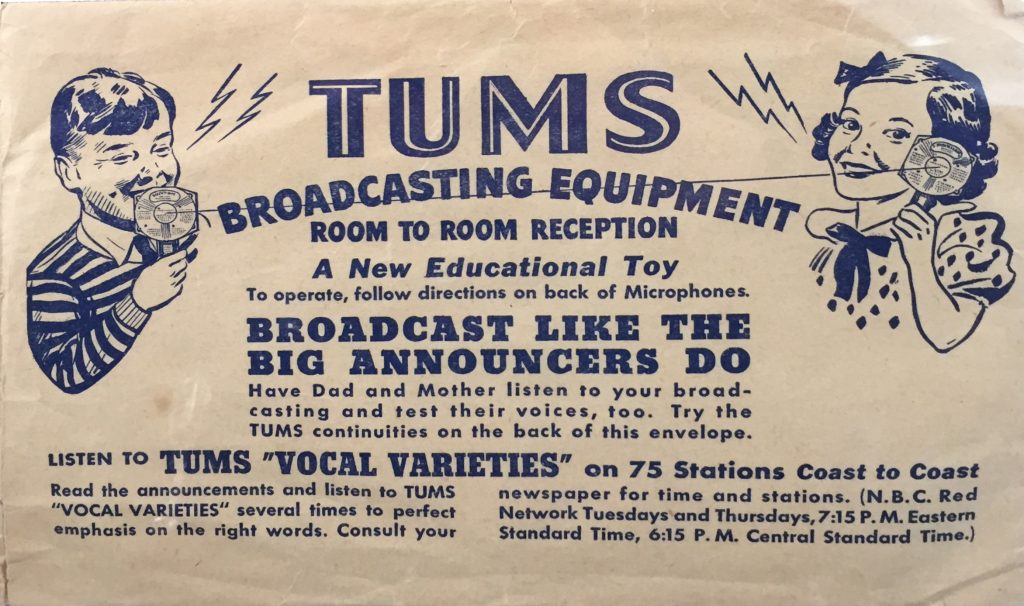

TUMS

This TUMS advertisement from the 1930s uses an "educational toy" to spread the word. Advertising had targeted children since the late 19th century, and contributed to the idea of "molding" children - a different kind of education in the world outside of school walls.

Source: Image taken by jaime ding.

Snow White

SSanitation Education heavily targeted candy wrappers, using them as examples of placing something where it is not supposed to go. The number of times candy wrappers were cited creates an image of the streets in the 1930s completely papered with them, though that generally was not the case.

Source: Snow White Chewing Gum, 1938. Closet Archaeology.

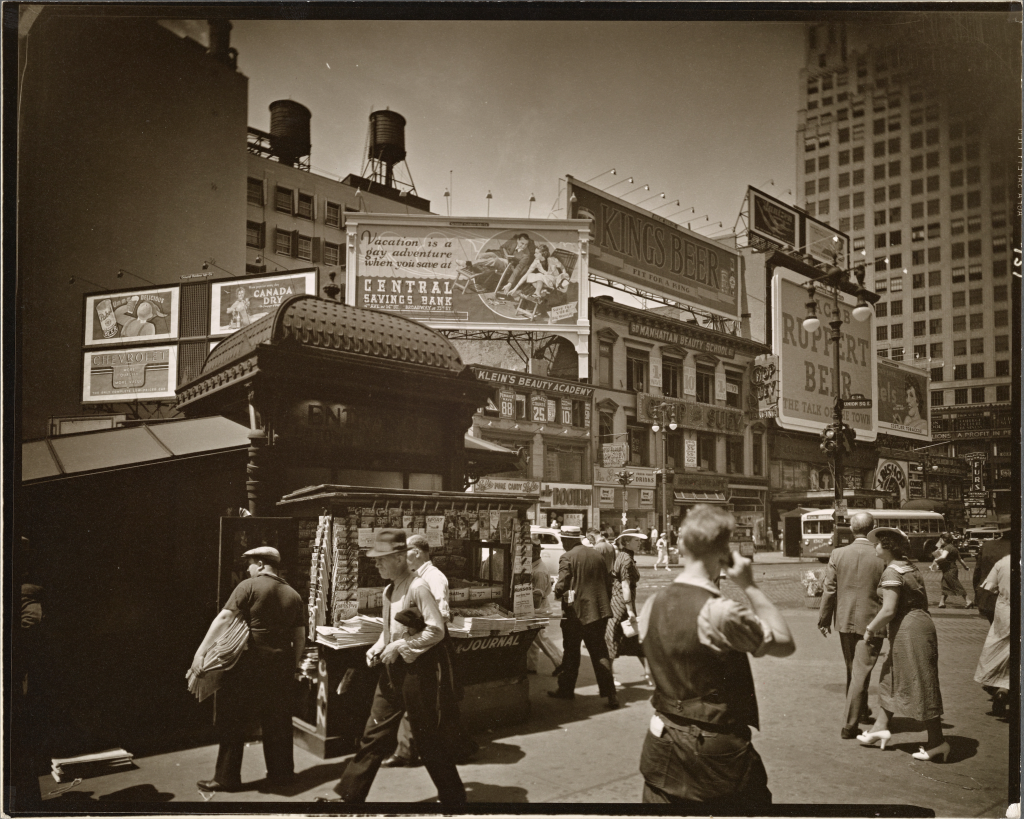

Subway Token

As New York City grew, the number of people, the availability of consumable items, and the methods of transportation grew as well. When the New York MTA opened, litter on the tracks became a serious concern.

Source: Bernice Abbott, "Union Square, 14th Street and Broadway, Manhattan." 1936, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. "Union Square, 14th Street and Broadway, Manhattan." New York Public Library Digital Collections. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-4ef6-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Token: The New York Transit Museum, photograph by Jaime Ding.

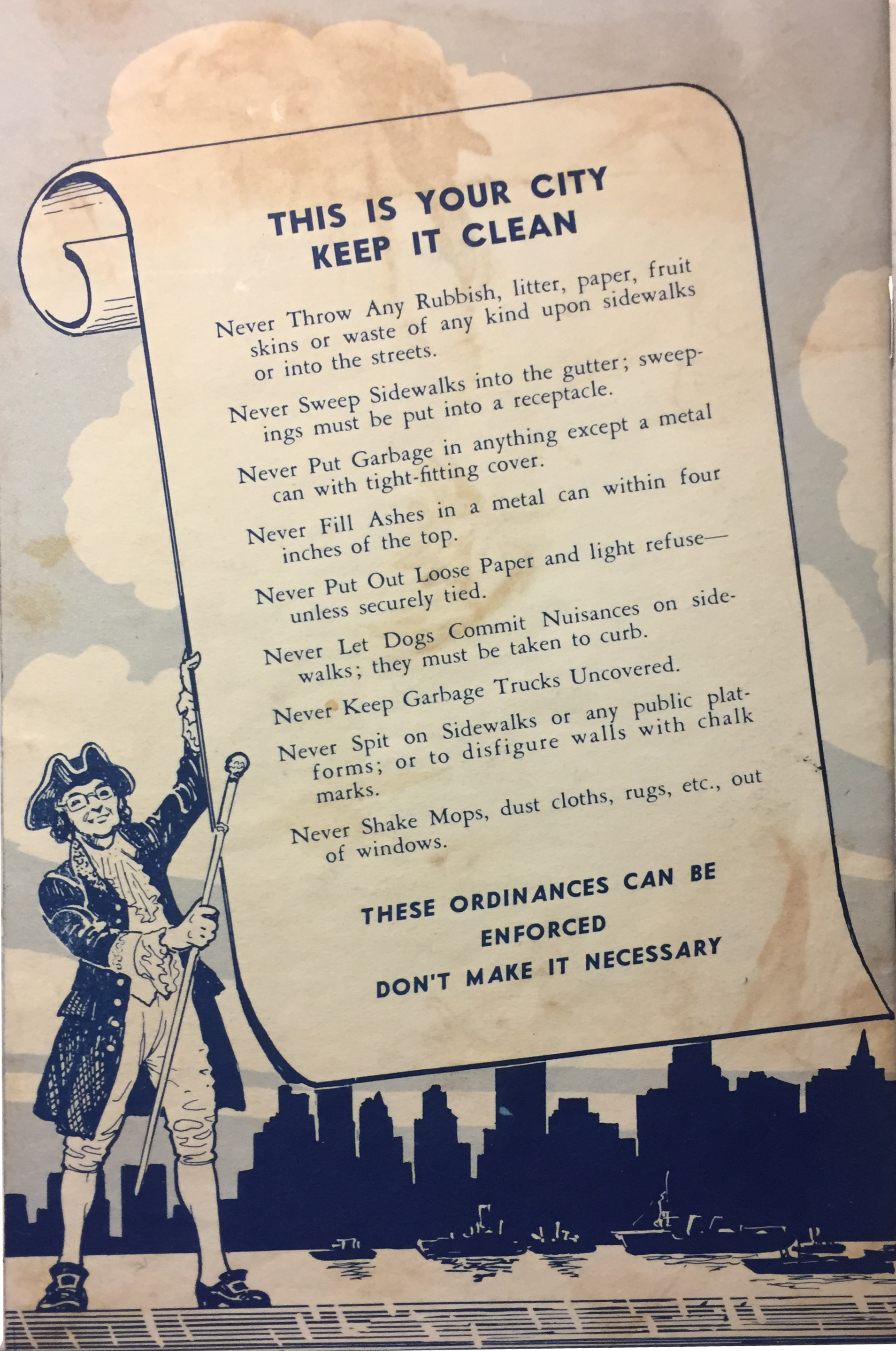

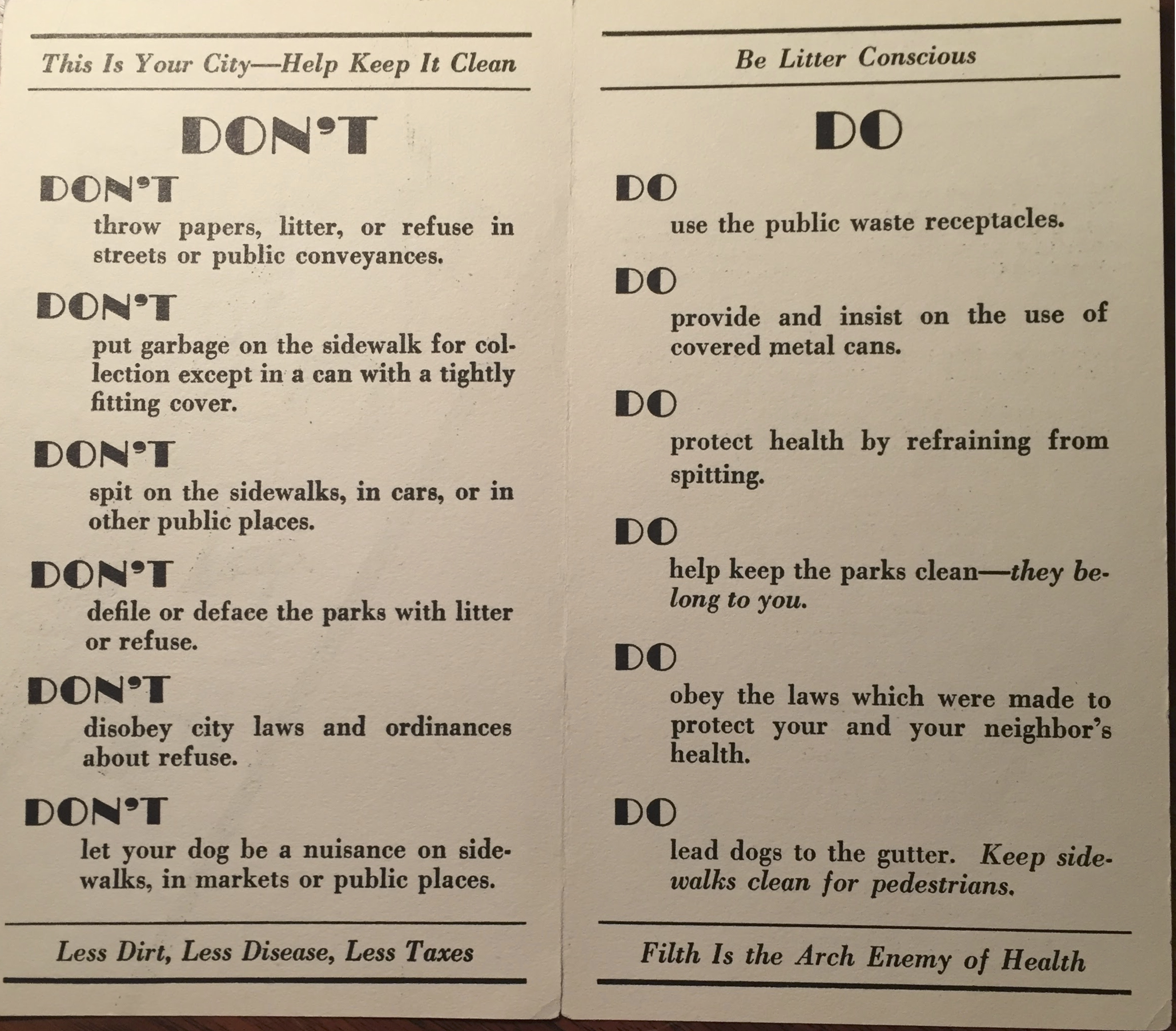

DON'T

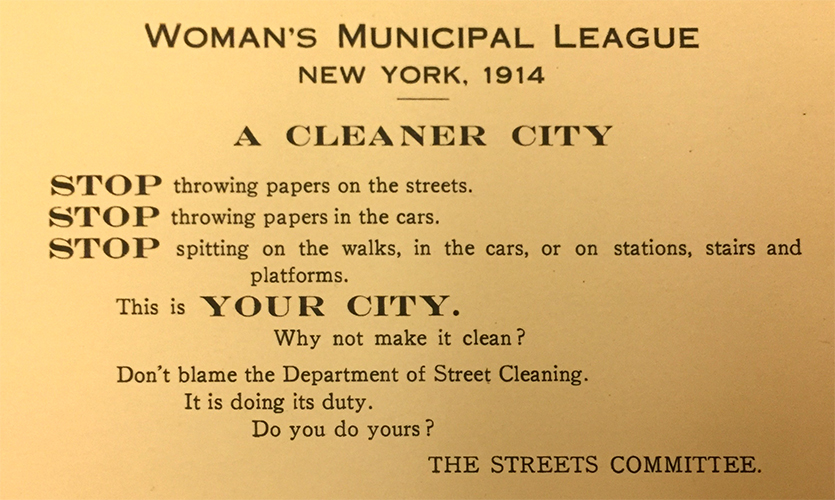

DON'T was a pamphlet passed out by the New York Academy of Medicine's Committee of Twenty on Outdoor and Street Cleanliness, a committee formed in the late 1920s to push for sanitation reform to promote healthy practices. The list of members on the back included wealthy academics and doctors such as H. Boardman Spalding, who also served on the Board at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Bernard Sachs, a neurosurgeon of the Goldman Sachs family. They took it upon themselves to educate the public as they saw fit, including this card, passed out to women in selected neighborhoods:

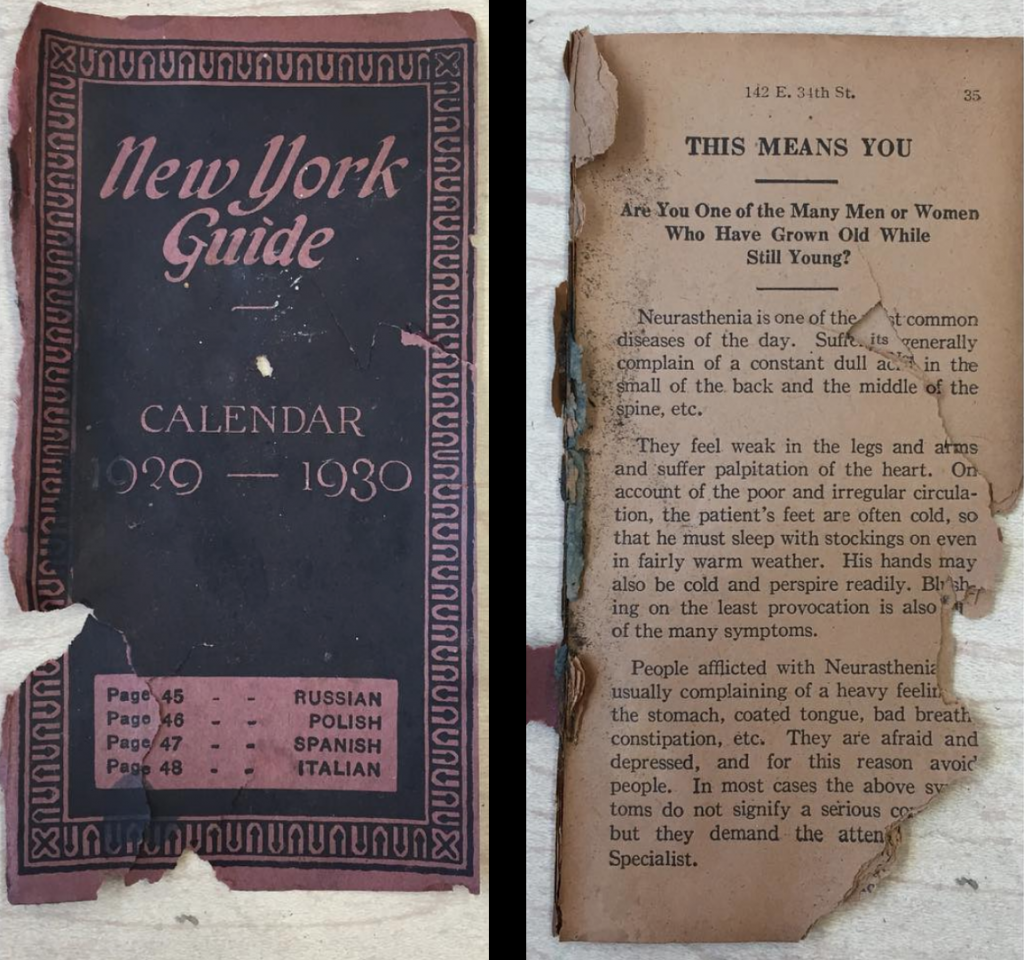

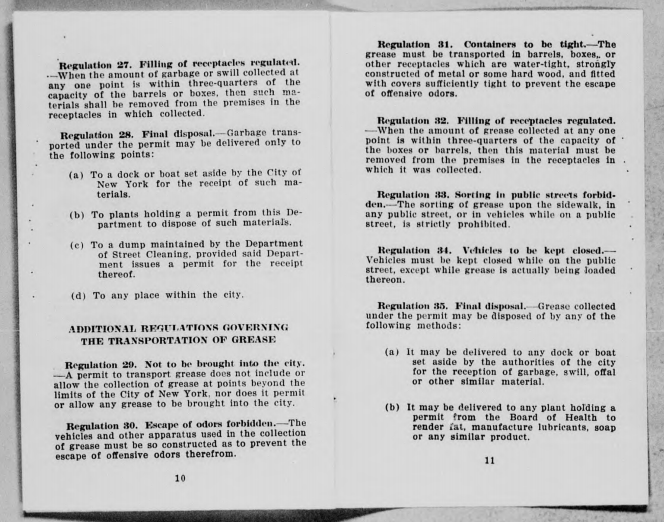

Sanitary Code

Click on the pages below to view the full Sanitary Code, with regulations about "Garbage and Swill," "Transportation of Manure," and "Butchers' Refuse and Bones."

Source: Correspondence of the Department of Sanitation, La Guardia and Wagner Archives, La Guardia Community College, New York City.

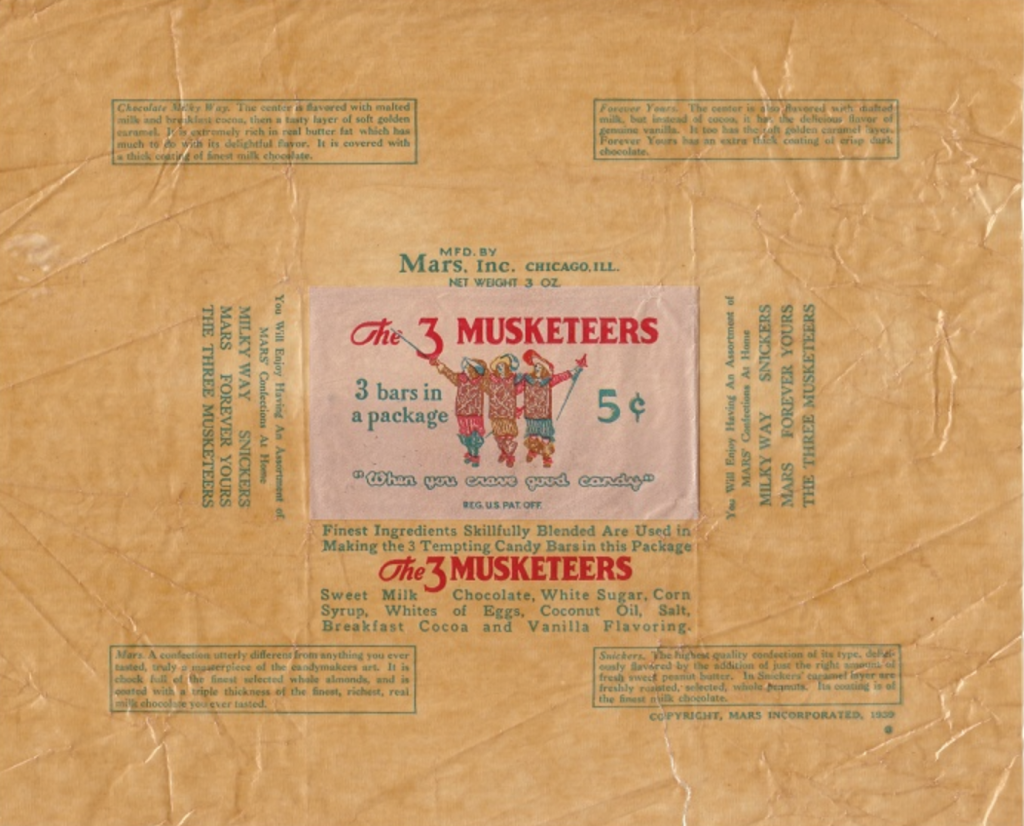

3 Musketeers

Sanitation Education heavily targeted candy wrappers, using them as examples of placing something where it is not supposed to go. The number of times candy wrappers were cited creates an image of the streets in the 1930s completely papered with them, though that generally was not the case.

Source: 3 Musketeers Wrapper, 1930s. candywrapperarchive.com

Matches and Ashes

In 1937, the federal government official prohibited dumping waste into the ocean, emphasis on burning unwanted materials stronger. Incinerators were a common sight in both residential buildings and businesses.

Source: 57th Street Liquor Store Matchbook, undated. Closet Archaeology

“I will refrain from throwing waste material upon sidewalks, streets, avenues, parks, and other public places, and will call attention of offenders to the laws against the throwing away or sweeping rubbish upon the streets and highways.”

Hundreds of Clean City League Inspectors signed and dated this pledge during the 1930s in New York City.5 Inspectors, public school students chosen by their teachers, “[warned] their classmates to not litter on the playgrounds,” and learned to shoulder the responsibility of keeping public spaces clean.6Not only were students taught to keep the spaces around them clean, they were also taught to see how others were not clean.

The New York City Department of Sanitation (DSNY) officially formed in December of 1929, a consolidation of all of the boroughs’ Departments of Street Cleaning and the division of Sewage.7DSNY included a subdivision titled Sanitation Education, run solely by Mrs. William F. Carey, the wife of the first Sanitation Commissioner.8 Sanitation Education taught the value of cleanliness as a part of an established curriculum, and rewarded prescribed behavior of future ideal citizens who would form a future ideal public. As a part of the “Cleanliness and Citizen Responsibility” Unit, Sanitation Education used a variety of media to teach children to think about what it meant to be clean, using more pledges, pamphlets, lectures, films, songs, plays, and slogan or poster contests.9 Those who demonstrated the most initiative for wanting their streets to be clean also were rewarded with power through Officer appointments, becoming President, Vice-President and Treasurer or aforementioned Inspectors.

More organized groups and clubs for young children and teenagers formed, all focused on keeping a litter-free, beautiful city: Junior Inspectors Clubs, Otis Youthbuilders, Anti-Litter Squads, Keep New York City Clean Clubs, and Clean City Leagues maintained an organized presence in public spaces, continuously reminding children and adults around them to put their trash in the right place. By 1938, the Junior Inspectors Club alone consisted of 88,379 members, all pledged to a “civic code of honor, designed to be a character building formula.”10They were featured on the radio station, WNYC, in newspapers, and at yearly celebrations, all following their slogan: “DO NOT LITTER THE STREETS.” Ironically, while Inspectors were expected to stop anyone giving out circulars in the streets, League responsibilities also included distributing circulars reminding residents of the Sanitary Code.11

Images of Sanitation Education.

Source: Department of Sanitation, City of New York. Annual Report 1938. NYC Municipal Archives Library, and Box 2, Outdoor Cleanliness Association archives, Manuscript and Archive Division, The New York Public Library.

These lessons learned not only were expected to reform students, but also were supposed to reform their parents. “Progressive Education” theories in the 1930s pushed for instruction to improve lives beyond reading, writing, and arithmetic. Schools aimed to transform and “Americanize” the lives of their students through initiatives such as free lunch and Pre-K.12 to improve “health, vocation, and the quality of family and community life.” 13Children of recent immigrants were particularly targeted, as their parents’ language barriers and different cultural customs were thought to prevent understanding cleanliness. Students in Harlem also garnered an disproportional amount of attention for their neighborhood and their efforts, not allowed to claim their “Americanness” without these lessons.

Sanitation Education needed to “Get at the Tendency to Do Wrong at Its Source and Replace It With the Tendency to Do Right.”14 Throwing trash out of windows, for example, a practice that was cited as a reflection on “slovenly” character, needed to be replaced with using designated containers.15 The “molding” of marginalized groups to shape a “Tendency to Do Right” was not necessarily to promote healthy living, but rather a preconceived standardized ideal of a responsible citizen.

Before the creation of DSNY, Colonel George Waring’s Department of Street Cleaning heroically cleaned up the streets of New York in 1895. The street sweepers were called White Wings because of their white militarized uniform which stood out on the streets. Colonel Waring prided himself on choosing the highest quality of men for his White Wings force, selecting them by their “snappy, clean, and wide awake” demeanor.16

During the Great Depression, the Department of Sanitation needed to appeal outside of city resources. Dr. William Schroeder Jr, the first Commissioner, almost immediately joined forces with private, civic organizations to clean and “beautify” the city’s streets.17 Though other departments of the municipal government attempted in the past to rally residents to clean up, the 1930s brought on an abundance of official efforts to clean up New York City. Emphasis on the “litter problem” highlighted the appearance of the city, hoping that a clean city would be the first step to a healthy economic city.

Sanitation Education not only taught children how to be clean model citizens,but also what spaces were their – an “Americanized,” civic-minded public – responsibility. Through events to clean up vacant lots, parades, picking up litter demonstrations, the lessons learned not only emphasized the categorization of things unwanted, but the specific containers they were to be placed in. 7,040 wire baskets, along with old oil barrels in market areas, dotted the streets by 1936. Their physical placement taught New York City citizens how to be “litter conscious.”18 Everyone needed to collectively claim ownership of the streets to make New York City a beautiful place. The people who walked through the streets of New York, expected to know what it meant to be a clean, civic-minded citizen, shared the responsibility of knowing which items went where.

♬ Driving Through Broadway at Daytime, circa 1930.

Source: Moving Image Research Collection, Digital Video Repository. University of South Carolina University Libraries.