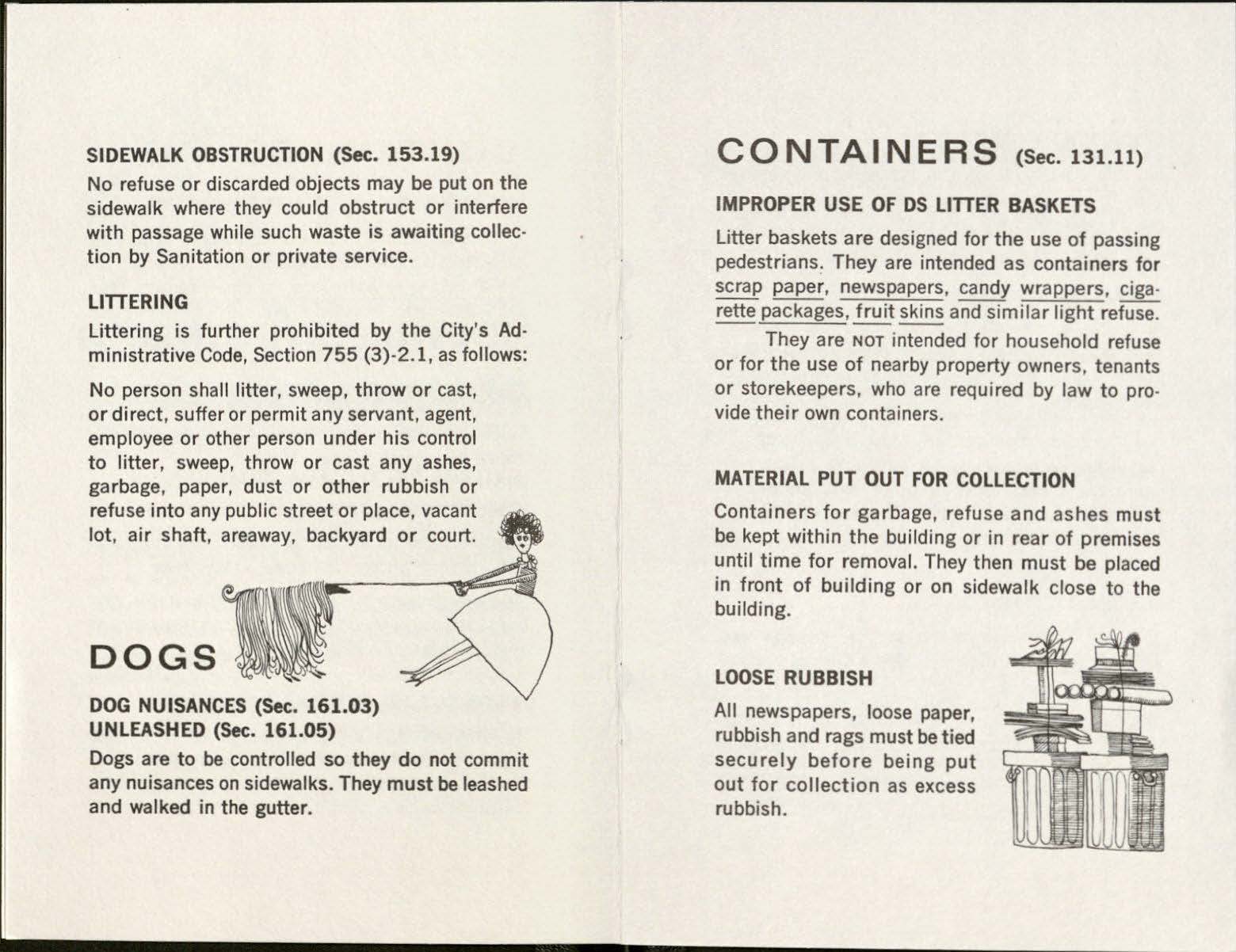

Digest of Sanitation Health Code

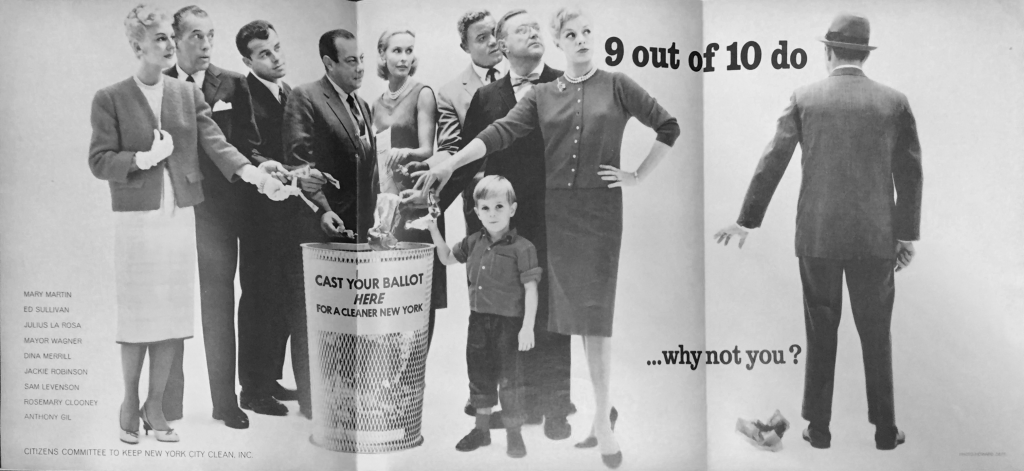

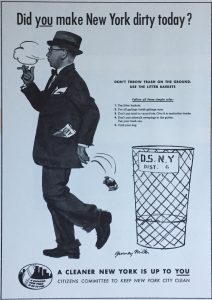

This pamphlet was handed out at the end of the 1950s as a part of the J. Walter Thompson agency's campaign, "Cast your Voice Here for A Cleaner New York." The image became plastered over signs, circulars, and trucks. The CCKNYCC cited it was voted the "best public service poster in the U.S."

In their correspondence in planning the campaign, J. Walter Thompson specifically targeted "problem" areas to strategize where to hand out the most pamphlets. Such problem areas were never specifically pointed out, though they referenced such areas as places where other languages were spoken.1

On the back, the pamphlet lists litter as "Public Enemies." Click on the excerpt to see the whole booklet:

Source: Annual Report of the Citizens Committee to Keep New York City Clean, 1960-1961.

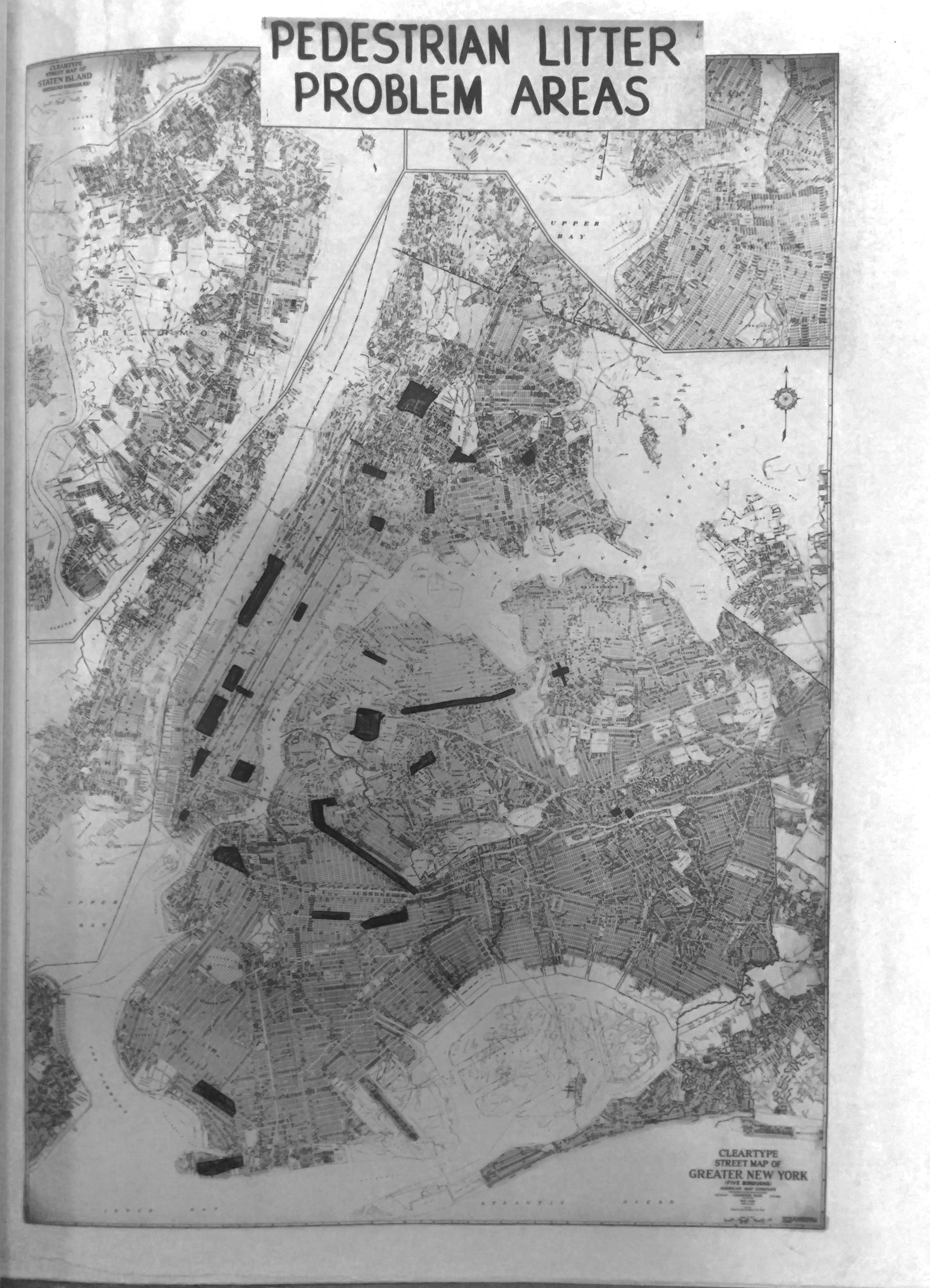

Problem Areas

Mayor Robert F. Wagner opened the 1957 Big Sweep with a speech, launching a 10-week campaign that included an intensive two-week educational emphasis on street cleanliness and events all over the city. A city-wide survey "located and recorded those neighborhoods which are in need of concentrated sanitary effort to improve these areas, as shown on attached maps." Big Sweeps continued for the next decade as annual projects, collaborations between the CCKNYCC and the municipal government.

Find the stick in the can for more information on Big Sweeps.

Source: "The Big Sweep, 1957." The Department of Sanitation, the City of New York. Municipal Archives of New York City.

The Big Sweep

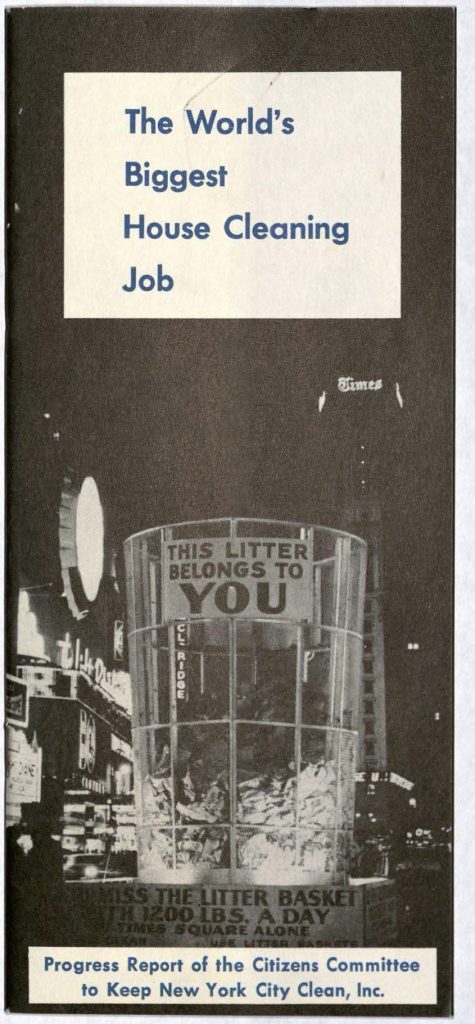

The litter basket stood as an important visible signal to attract attention, clearly demonstrated through 30-foot-tall cans such as this one. As campaigns took off, these large markers became icons set in pedestrian heavy areas to remind people that litter baskets were available for use.

Mayor Robert F. Wagner opened the 1957 Big Sweep with a speech, launching a 10-week campaign that included an intensive two-week educational emphasis on street cleanliness and events all over the city. A city-wide survey "located and recorded those neighborhoods which are in need of concentrated sanitary effort to improve these areas, as shown on attached maps." Big Sweeps continued for the next decade as annual projects, collaborations between the CCKNYCC and the municipal government.

Find the "Problem Area" map to learn more about Big Sweeps.

Source: Department of Sanitation, NYU Museum Sanitation Project Archive.

Annual Report, 1960

The Citizens Committee to Keep New York City Clean began publishing their Annual Reports not only for current members but potential members. Formed in 1955, CCKNYCC carefully designed their annual reports using images of neatly contained trash. Inside, stylish graphs and happy demonstrators showed measures of success, effectively self-congratulating readers on a job well done without getting dirty themselves.

This recreation of a litter basket in the 1950s is based off of this clean image.

Source: Annual Report of the Citizens Committee to Keep New York City Clean 1960-1961. New York City, 1960.

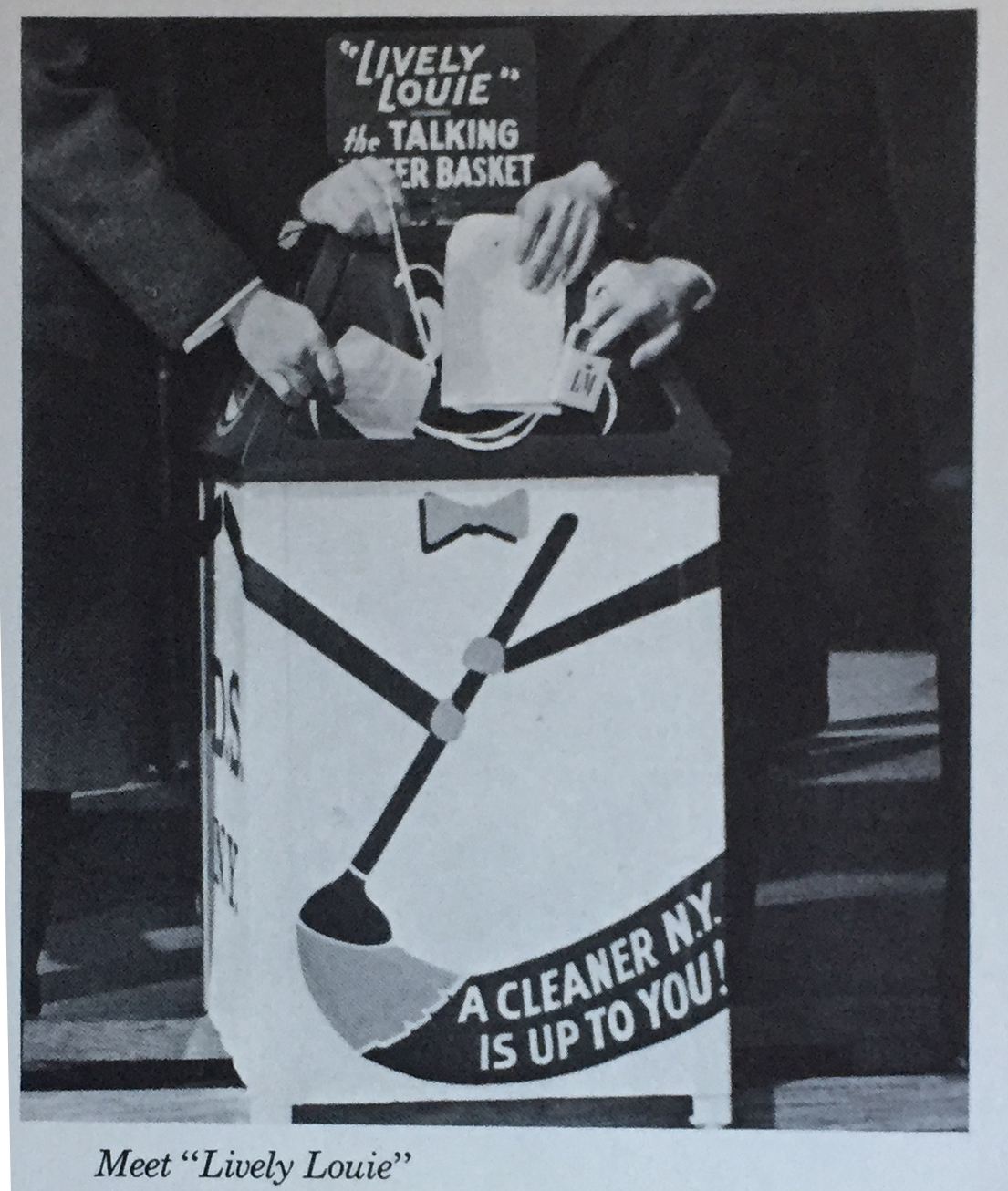

LIVELY LOUIE

First placed in the middle of Times Square, Lively Louie was hooked up to an intercom system, and Sanitation men hid around nearby corners and called out to passerbys to not throw litter on the street. Lively Louie became so popular that he was placed in every borough. The stunt was another attempt by Young & Rubicam to draw attention to litter baskets.

Eventually, Louie traveled to other parts of the country, as evidenced by this basket in Greenville, North Carolina:

Source: Clean City, USA: A Record of the Activities of Young & Rubicam as Volunteer Advertising Agency for Citizens Committee to Keep New York City Clean, Inc. May 1955-July 1959.

"Lively Louie" the talking litter box. April 21, 1958. The Daily Reflector Image Collection. East Carolina University.

Clean Streets

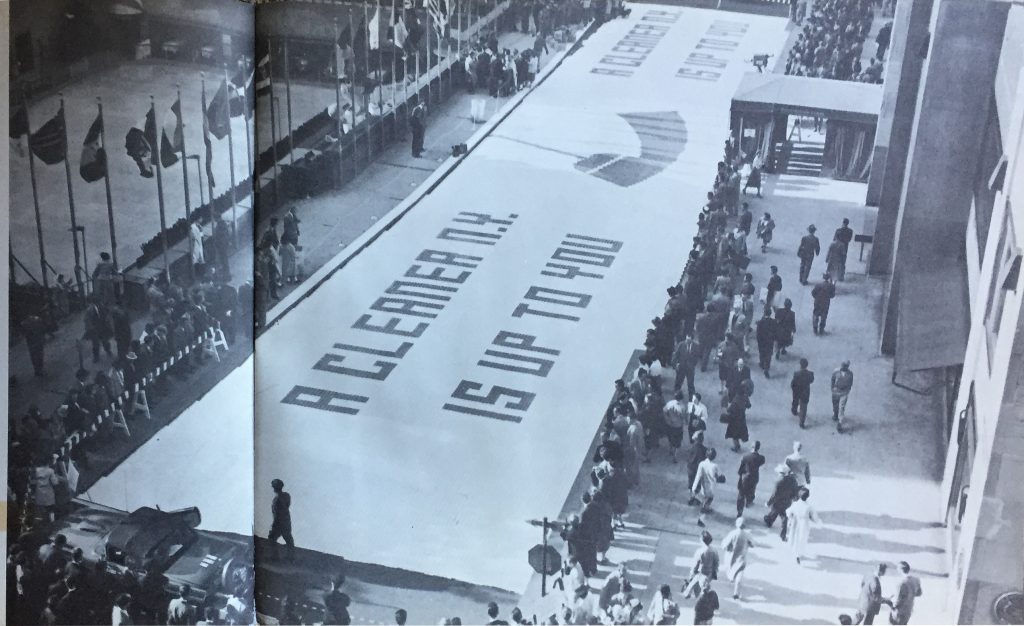

In October, 1956, 108,000 bars of soap, donated by a large soap manufacturer, covered the block in front of Rockefeller Center.

CCKNYCC saw the spectacle as a celebration to begin the second year of their mission to create the "cleanest big city in all the world." The attention-grabbing event allegedly helped boost the city's cleanliness rating from 56% in 1955 to 69% at the end of 1956.

Source: Clean City, USA. A Record of the Activities of Young & Rubicam as Volunteer Advertising Agency for Citizens Committee to Keep New York City, Inc., May 1955-July 1959

This Litter Belongs to You

Click on the pages below to learn more about the "World's Biggest House Cleaning Job."

Source: Box 7, Special Projects Series, Howard Henderson Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.

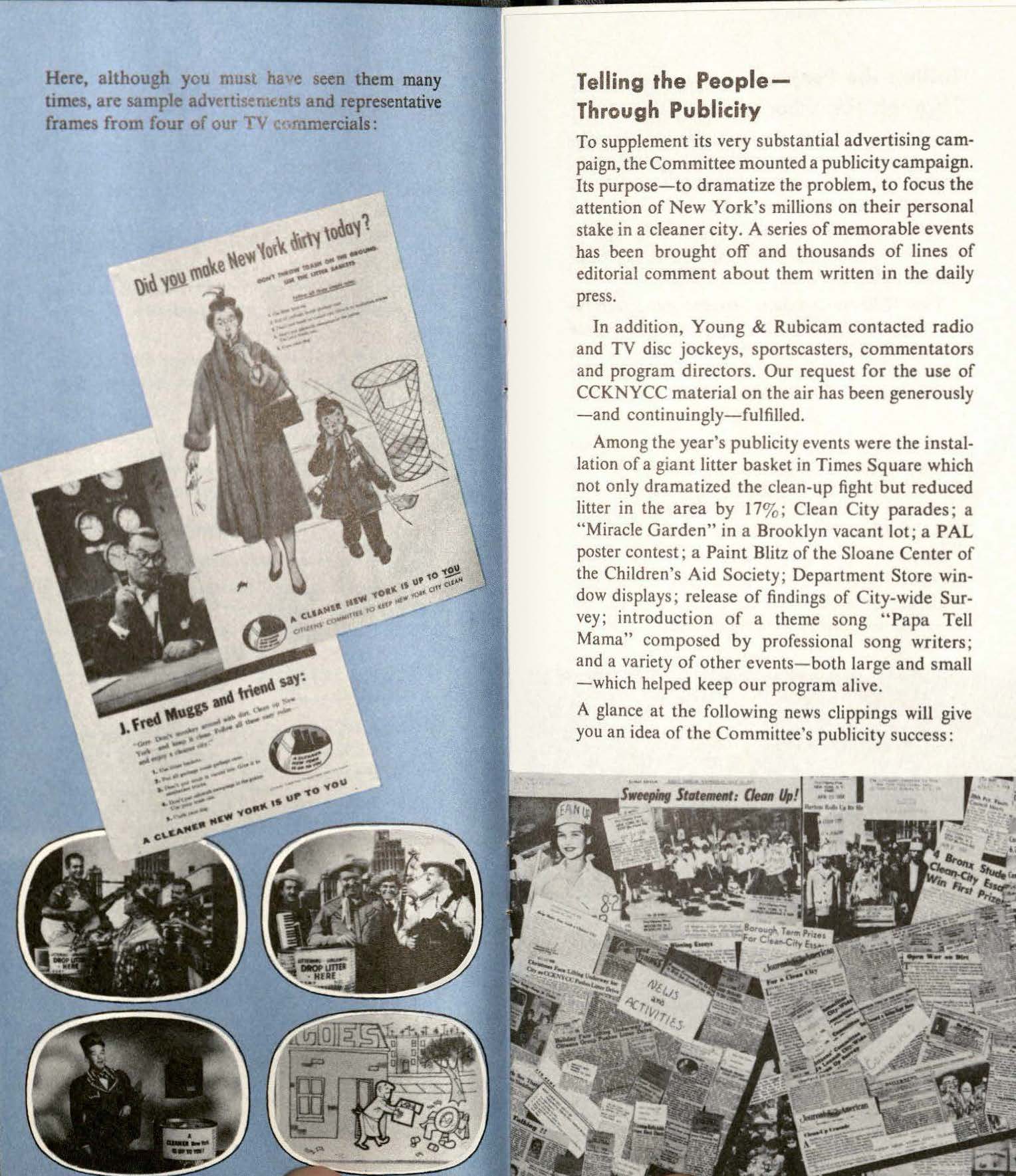

Advertising Campaigns

Advertising campaigns, a private contribution to a municipal department, was an extension of the school campaigns that had been happening for years in Sanitation Education. Many of the advertising agencies (all working pro bono) believed that their influence on children's personal cleanliness was the watershed moment in changing how the city looked. Howard Henderson, the president of J. Walter Thompson, believed children were to be an advertising 'medium,' a gateway to communicating to parents of "troubled areas."2However, the publicity of the campaigns was prioritized over in-classroom education with emphasis on visibility of the issue beyond classroom walls. The litter basket became an icon. For JWT, this was logical as a "democratic campaign" for the consumer for 3 reasons:

- we are attempting to educate people to deposit litter in a specific place - so, we must have the place.

- we attempt to identify (classify) the litter in order of its quantity - for example, scrap paper, cigarette and candy wrappers, etc.

- we attempt to show them the "rewards" for depositing litter - or, "what's in it for them."

Other advertising agencies also targeted the individual's civic responsibility: Y & R launched The Big Sweep, citing a "Cleaner New York is Up To You." Ogilvy, Benson & Mather and BBDO launched the friendly Phil D. Basket.

Source: Annual Report of the Citizens Committee to Keep New York City Clean, Inc. New York City, 1962.

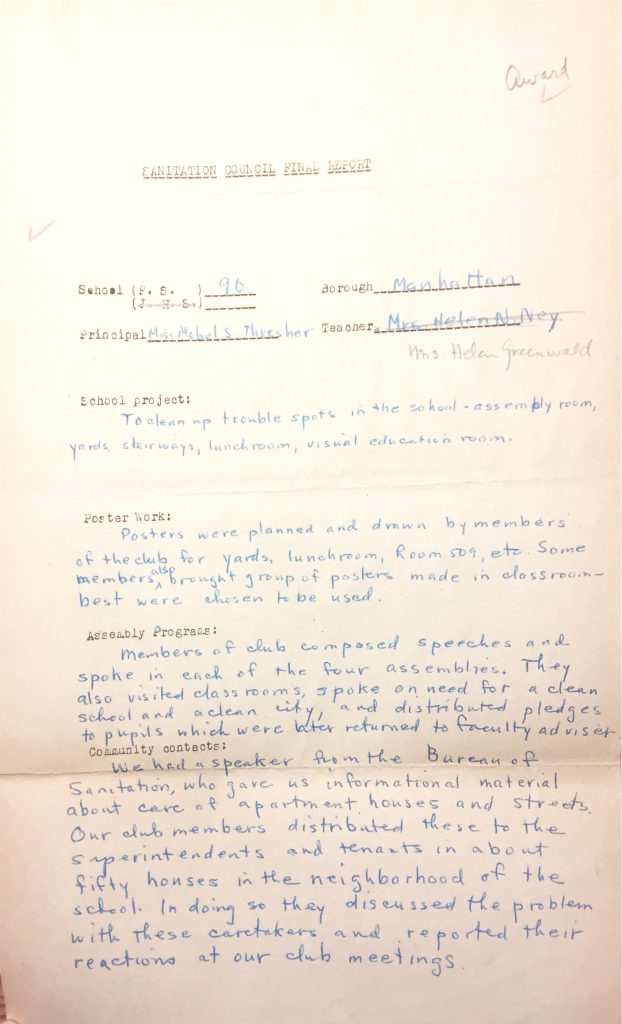

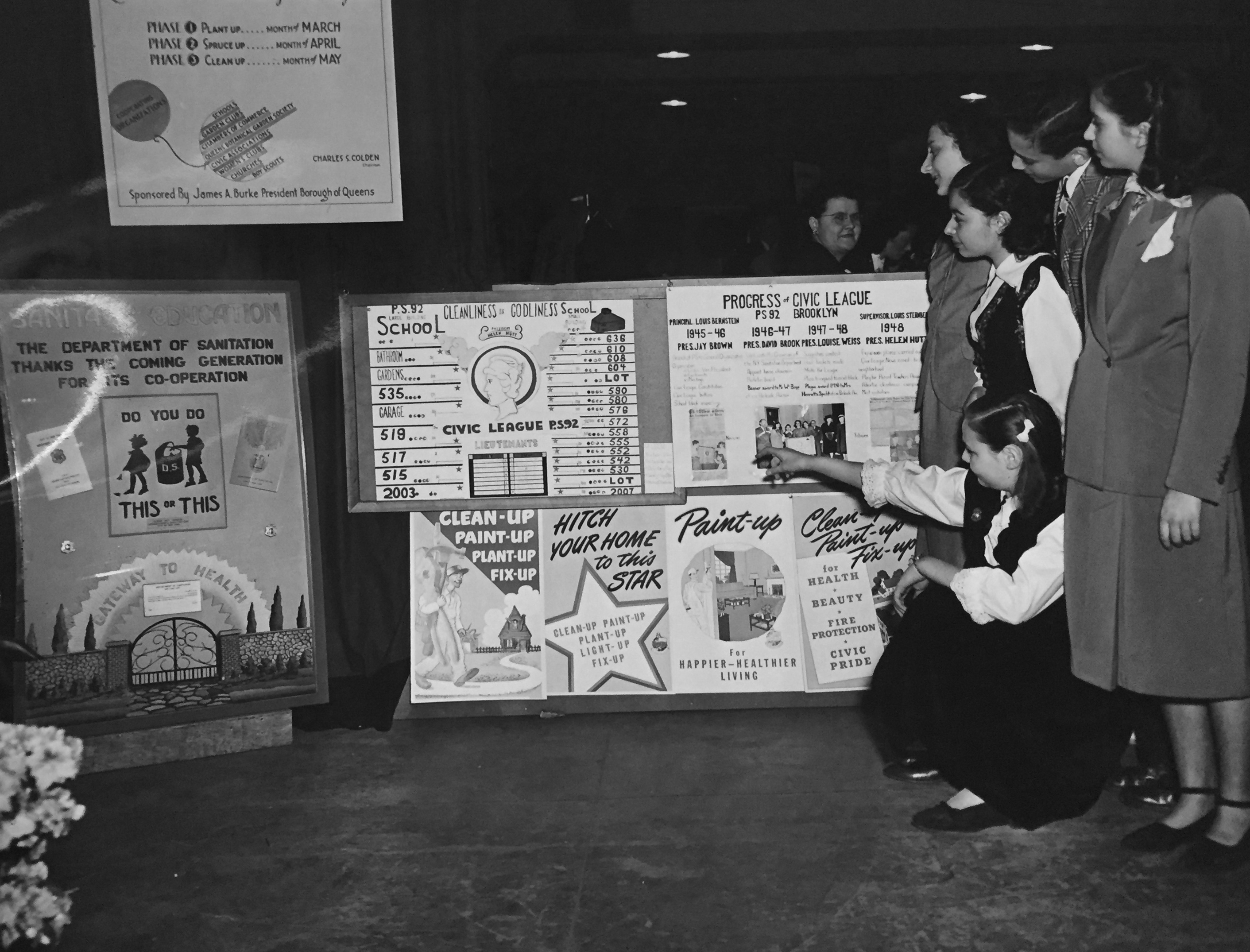

Award-Winning Schools

P.S. 90 on 225 W. 147th Street in Manhattan, along with P.S. #35 on Decatur Street and Lewis Avenue in Brooklyn, won the award for being the Most Outstanding Cleanliness school for the 1946-1947 school year. The following year, the Outdoor Cleanliness Association announced the winners over the radio station 710 WOR in September. The winner was chosen on the basis of having "outstanding clean-up projects" and results. The prize was a banner presented to the school and its members of the Otis Youthbuilders club at a school assembly.3

See an example of poster contest winners from PS 92 in the 1950s below:

Source: Box 7, Outdoor Cleanliness Association records, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Parent Aids

As children were seen as a strategy to influence parents, so many of the things children were to take home were also directed at their parents. Sanitation Education expected parents to aid their children, just like multiplication or reading. Compare the pledge above to the card stating the Sanitary Code below, both from the OCA.

Source: Box 2, Outdoor Cleanliness Association records, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Multiplication Aid. 1958. See the back of the Aid here: Closet Archaeology.

Beer Cans

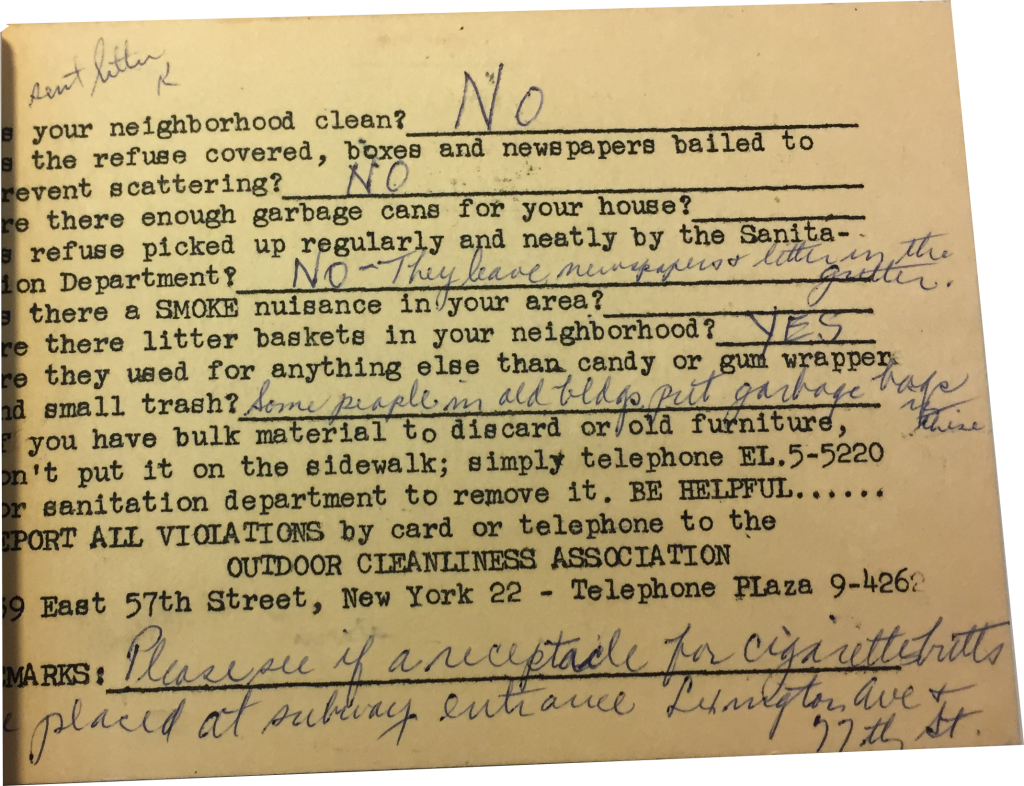

The OCA mailed cards to neighborhoods to survey residents about the cleanliness of their neighborhoods.The Outdoor Cleanliness Association collected complaints from select areas, and reported them to the Department of Sanitation. As the middleman, the OCA had the privilege of access to the municipal department and leveraged this position of power. Their close relationships with not only the Sanitation Commissioner, but also the Police, Health and Parks Commissioner, allowed them the privilege of access - an ease to simply send a letter about certain circumstances, expect and receive a reply.

Here, you can see a member of the OCA wrote "beer cans," on the list of the complaints. One complaint is from a "(Very fashionable neighborhood)"; another, "no attention paid to improving conditions."

For members of the Outdoor Cleanliness Association, improved conditions would be like this "Chalk Carpet of Color Contest" in 1956:

Source: Box 8, Outdoor Cleanliness Association records, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Best of Everything

Novels like The Best of Everything portrayed New York City as a bustling city, one where anyone could make their dreams come true.

As a popular novel that soon became a movie, the story reveals not only the perspectives of five

20-something young women but also the things in the city and how they were treated in the city.

A paper cup was retrieved from the grocery store full of orange juice.4 A girl, on an investigative

hunch, sorts through trash and finds "three cigarette butts, one with lipstick on it, an empty lipstick case, a torn piece of a letter."5

Source: Photograph by jaime ding.

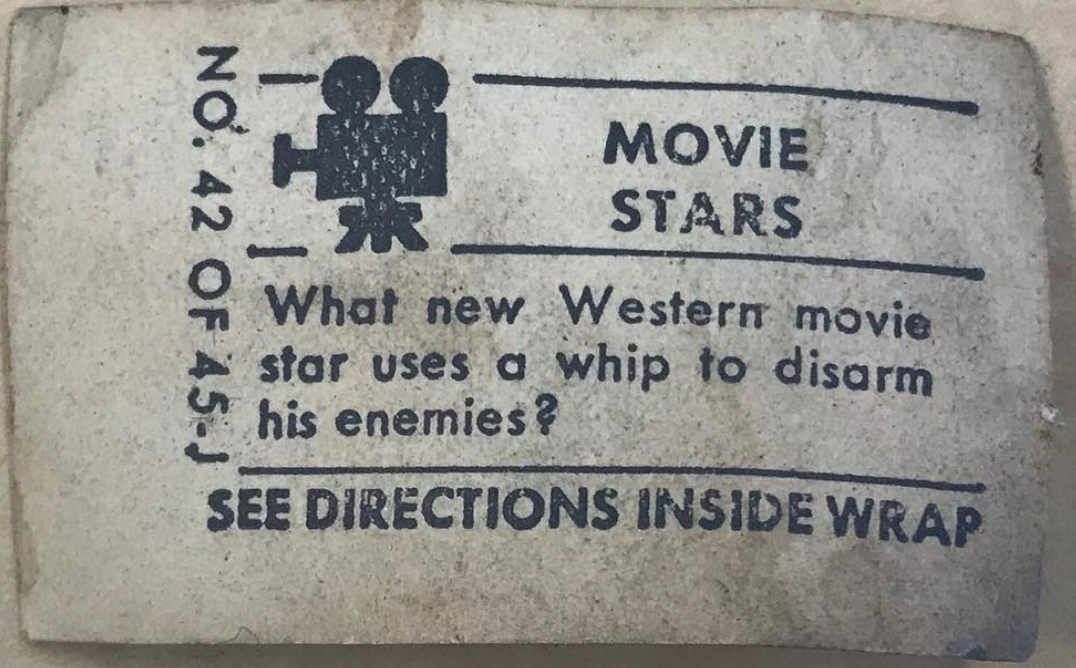

Movie Star Trivia

Like many other packaging materials in the 1950s, advertising campaigns for sanitation used celebrities and star power to popularize their campaigns. Local celebrities like TV legend Hugh Downs and Ed Sullivan, Mary Martin, Jackie Robinson, and Sam Levenson all were posed as "somebodies." The celebrities showed "ordinary" people how to be successful people - to not be a "nobody," but be a part of the "somebodies."

Source: Clean City, USA: A Record of the Activities of Young & Rubicam as Volunteer Advertising Agency for Citizens Committee to Keep New York City Clean, Inc. May 1955-July 1959.

Gum paper from Closet Archaeology.

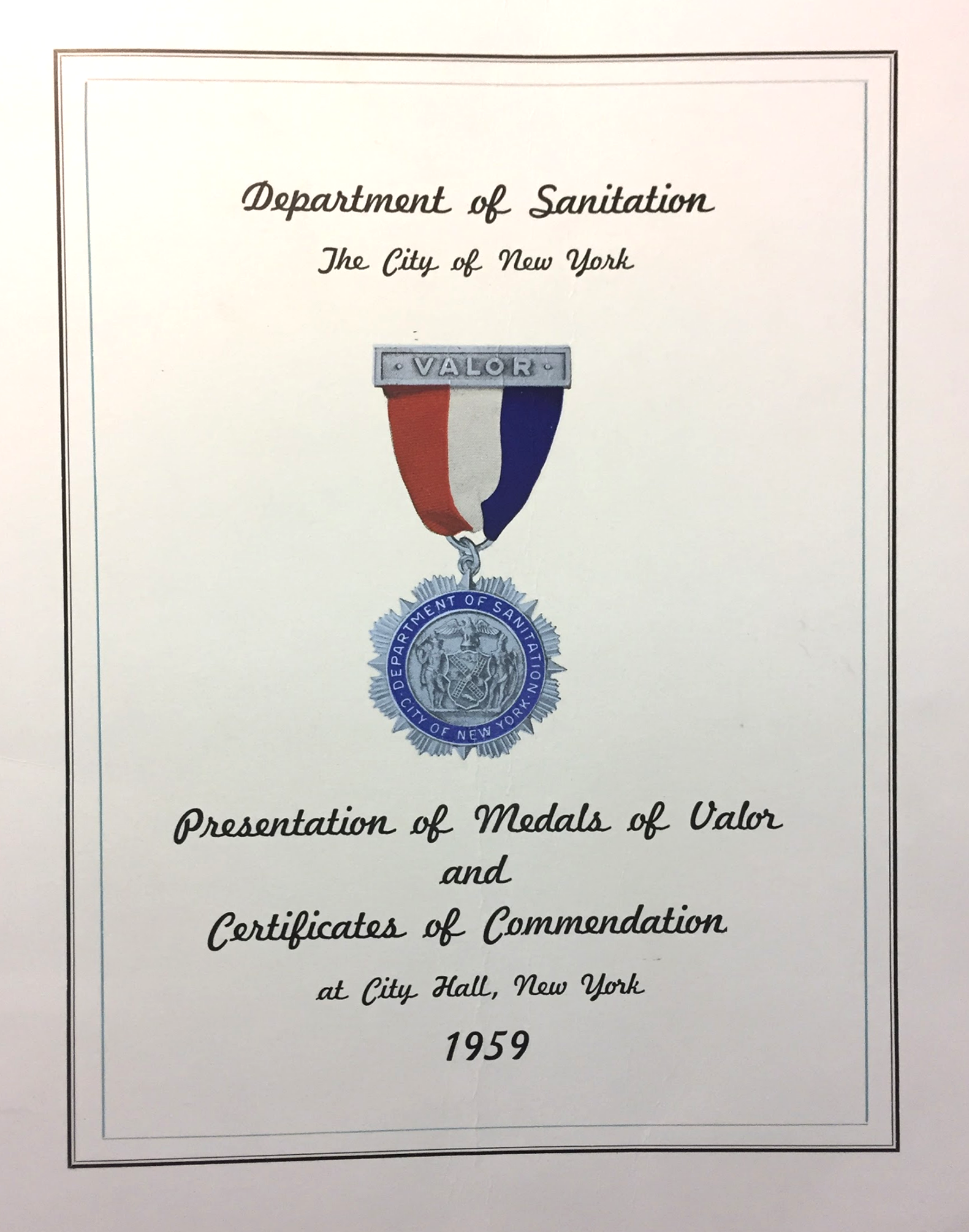

Municipal Housekeeping

The Outdoor Cleanliness Association (OCA) followed many other female civic organizations in comparing the streets to spaces in their homes, stating street cleaning was a "municipal housekeeping" task. The OCA often sponsored clean-up demonstrations, usually with brooms. However, like many of their events, demonstrations served as a social event rather than one to clean up the city.

Other social events included the presentation of medals to members of the Department of Sanitation:

Source: Box 8, Outdoor Cleanliness Association records, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

"Put Litter Here"

3,400 new litter baskets were ordered by the city in 1958, all with signs that advised people to "Put Litter Here." These litter baskets were white and supposed to attract attention. With the new additions, a total of 25,000 baskets were put "strategically" on the streets. The goal was to supply a basket for at least each 100 feet of curb.6

As advertising agencies promoted their own campaigns, the words on the litter baskets changed. Once J. Walter Thompson launched their campaign to "Cast Your Ballot Here," the litter baskets also reminded passersby to do so. Of course, the glamorous clean litter baskets did not reflect the actual labor of cleaning up the streets.

Source: Litter basket images; Clean City, USA: A Record of the Activities of Young & Rubicam as Volunteer Advertising Agency for Citizens Committee to Keep New York City Clean, Inc. May 1955-July 1959.

Photograph of Street Sweeper; United States. Office of War Information / Museum of the City of New York. 90.28.14

The Middle(wo)man

The Outdoor Cleanliness Association mailed cards to neighborhoods to survey residents about the cleanliness of their neighborhoods. They received responses like this one from concerned citizens and would write a letter to the Sanitation Commissioner. (Find the beer cans in the trash to see an example). As the middleman, the OCA had access to the municipal department and leveraged this position of power.

Source: Box 8, Outdoor Cleanliness Association records, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Did you make New York dirty today?

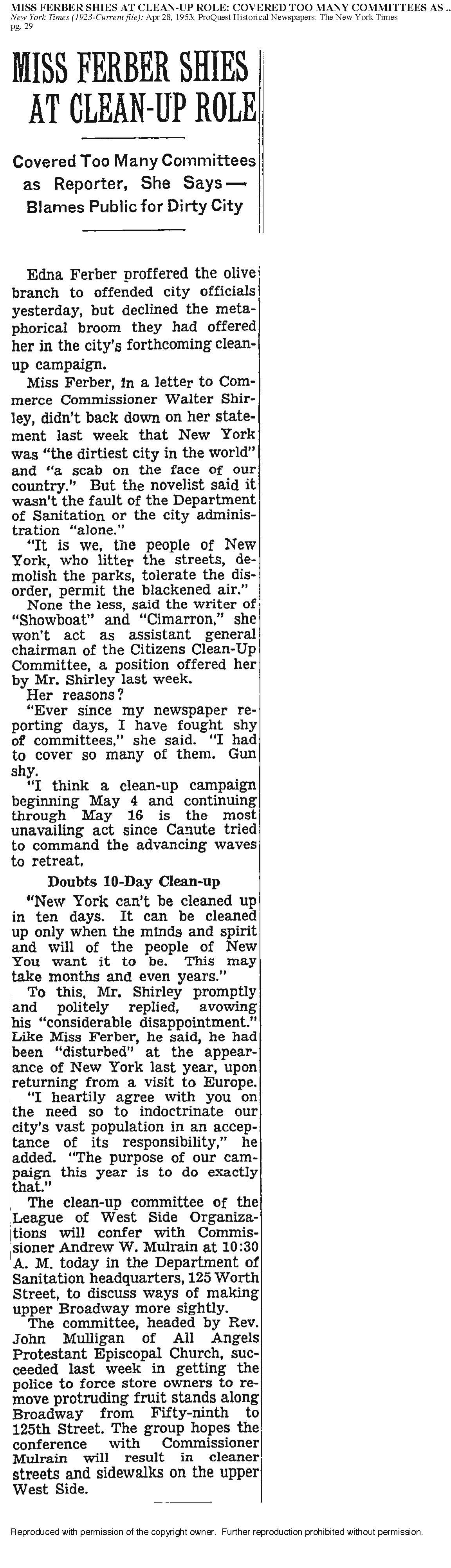

When novelist Edna Ferber declared that New York was “the dirtiest city in the world and a “scab on the face of our country”, some New Yorkers turned waves of outrage into action to try to change such a reputation. Groups of wealthy, white private organizations sponsored huge public campaigns, mostly to show their efforts to clean up the city visible, and hence viable.

Though private organizations had always contributed to municipal efforts, the 1950s brought tens of thousands of dollars spent on huge advertising campaigns, created by the flourishing ad agencies on Madison Avenue. These agencies run by men overshadowed previous efforts, efforts predominately organized by women. Members of these organizations were people in powerful positions as heads of companies or on boards of institutions, and held close connections to politicians and commissioners of the municipal government. They comfortably assumed that the municipal government was there to serve them, and, moreover, they did not see themselves as a part of the problem. Through these campaigns, those who could afford to throw away more and already expected others to clean up after them distanced themselves from the imagined “dirty publics” who did cause the problems as the righteous citizens who “really cared for their city.”7

Campaigns such as “A Cleaner New York Is Up To You!” emphasized the collective responsibility of taking care of the city. However, the intent behind the “You!” targeted particular neighborhoods – particularly “problem areas” such as the Lower East Side, the South Bronx, Harlem, and Brooklyn, where residents were thought to be filthy and a nuisance.8

In reality, these neighborhoods not have equal amount of municipal resources dedicated to them as “non-problem areas” did.9Those with the most responsibility for caring for public spaces while having less access to resources made up the “dirty public,” separate from those who did have access, power, and wealth – the self-determined clean, generous, and caring model citizens.

“The people themselves have also been transformed.”10See how these private organizations have – or have not – transformed dirty publics.

The Outdoor Cleanliness Association, or the OCA, formed in 1930 with the aim to raise awareness for cleanliness in the city.11 Consisting of solely wealthy white women in the Upper East Side, the OCA was one the most active and influential private citizen groups, working with the Department of Sanitation in Sanitation Education and public relations. 12 This immense amount of organizational effort can be seen through the preservation of an archive donated on February 1, 1971 by Mrs. Charles Gristede, the daughter-in-law of the founder of the Gristedes supermarket chain, to the New York Public Library.13

Members divided into Committees that focused on certain cleanliness issues, such as the Block Committee (who made sure that blocks would have “neat and orderly premises”) and the Dog Committee (who, allegedly, came up with the phrase “Curb Your Dog”).14These wives of wealthy businessmen and bankers gathered membership fees to print ephemera such as pamphlets, certificates for the cleanest children, and cards that stated “Please THROW Cigarettes, Chewing Gum, Papers into Litter Basket. SWEEP Sidewalk Rubbish into Trash Can” used in educational programs.15In 1947, over 25,000 “Civic Pride in Your Home Town” booklets were distributed to public schools across New York City. Hundreds of principals wrote to the OCA (with every letter addressing the OCA as “Sirs”) requesting the booklets in order to “educate the children as to how to be good housekeepers out of doors.” They believed that informing “every man, woman, and child, can do his part to help keep the city clean and improve the health of the community.”16

Dog Comfort Station Launch, 1957. Source: Outdoor Cleanliness Association records, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, New York City.Such efforts to maintain control over the city streets often patronized other citizens with the inherent assumption that no one else knew how to be clean.17The OCA planned community events to encourage caring for the city, directing resources to initiatives that helped neighborhoods become aesthetically beautiful. They often took advantage of their close relationships with the Sanitation Commissioner, the Police Commissioner, Health Commissioner, and Superintendent of the Department of Education, the OCA often used their connections. Invites to annual Flower Marts, clean up demonstrations, and Sidewalk Chalk contests used municipal time and energy that ignored other infrastructural needs. The OCA campaign for “reducing dog nuisance,” for example, prompted the expensive $500 solution of “Dog Comfort Stations, paid for by taxpayer dollars through the Department of Sanitation.”18Many of the registered dogs in the city were poodles, a popular trend for women in the Upper East Side.19

The OCA also sponsored a Junior Outdoor Cleanliness Association, a largely social group that organized dances and helped out with the Flower Mart, effectively teaching Junior members how to live like OCA members in being “clean in every possible way” – a good citizen needed to smell good, look good, and be proud of being good.20. As larger groups such as the Citizens Committee to Keep New York City Clean and Keep America Beautiful came onto the anti-littering scene, the OCA disassociated in 1969, overshadowed by the louder language from other groups.

Efforts in cleaning up neighborhoods of New York City did not solely rely on benevolent Upper East Side white women. Residents of Harlem and Brooklyn like Bessie Buchanan and Shirley Chisholm, were fighting through political avenues for the same amount of access and attention that “nicer” neighborhoods received from the government.21 Though their records may be as clearly accessible like the Outdoor Cleanliness Association, their work was still there.

Is Harlem really a “problem area”? Source: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. “Bird’s eye view of West 125th Street, Harlem, looking west from Seventh Avenue, 1943” New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Throughout the 20th century, many white private citizen groups attempted to solve the city’s problems. Groups like Citizens for Clean Air, the City Gardens Club of New York City, the Women’s Municipal League, the Clean Sidewalks Association (which eventually merged with the Outdoor Cleanliness Association), the Fifth Avenue Association, the League of Women Voters, the Federation of Women’s Clubs, Committee of 500, and the Committee of Twenty on Street and Outdoor Cleanliness, all aimed to beautify New York City, long before the Citizens Committee to Keep New York Clean (CCKNYCC) or Keep America Beautiful.22

In 1953, Keep America Beautiful, was founded also by corporate and civic leaders. As a nation-wide campaign, Keep America Beautiful advocated to get “rid of the ugly litter now defaming the nation’s highways, the streets of cities and towns, the pleasure of parks and beaches.”23The non-profit was led by William C. Stolk, the president of the American Can Company, along with other industrialists who created disposable products. They, the head executives of food, forest products, steel, tobacco, rubber, chewing gum, soft drinks, and candy, termed themselves the “Responsible people,” ones who were the strongest and most noble people to do something against “too great odds.”24 KAB tried to change the effects, but did nothing to change the cause.

Though women work for years, the 1950s brought to light a new group for “Municipal Housekeeping,” the Citizens Committee to Keep New York City Clean (CCKNYCC). In 1955, Mayor Robert F. Wagner asked Keith McHugh, the president of the New York Telephone Company, to organize a citizens committee, filling in services that the city could not completely provide.25Men in powerful positions such as Harold W. McGraw (of McGraw Hill Companies), and George D. Busher (the former president of the Bronx Real Estate Board) along with a few select women, such as Miss Dorothy Shaver (the President of Lord & Taylor) had decided to take it upon themselves to take up the challenge of making the city clean, a role that could help gain political leverage. Later, for example, Chairman McHugh became the New York State Commissioner of Commerce in 1959.26

Sigurd S. Larmon, the head of Young & Rubicam (Y&R), became the Public Information and Education Committee Chairman. A flourishing Madison Avenue advertising agency who gained fame from Jell-O and Gulf Oil, Y&R launched the first commercial campaign to help the Department of Sanitation clean up the city.27The campaign, a “War on Litter,” focused on making litter baskets visible, with city-wide stunts such as “Big Sweeps.” Y&R aimed for a glamorous version of being clean, expanding from educational films to TV commercials with catchy songs and famous celebrities. Ella Fitzgerald was commissioned to sing “A-Tisket A-Tasket,” with the lyrics changed to “Please use the litter basket. / Oh, please don’t scatter dirty matter, Put it in the basket.”28

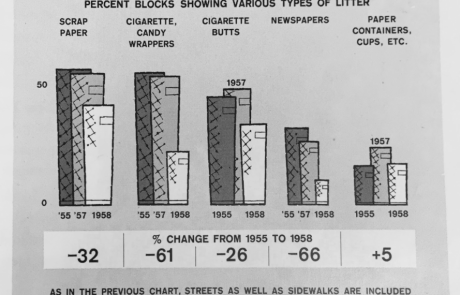

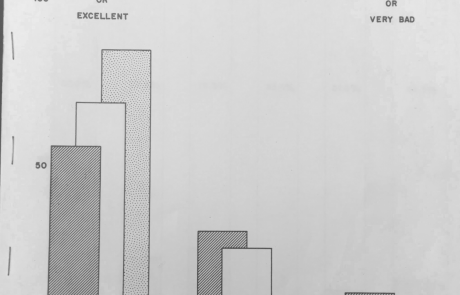

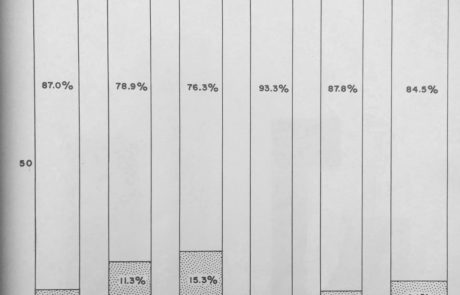

The ad agency also published large Annual Reports each year for not only CCKNYCC members but also for recruitment. However, much of the actual reporting in the Annual Reports were largely ornamental. The change between clean and dirty sidewalks, effects on campaigns, or any other statistical references never had any evidence that was not circumstantial. Graphs had no scales, and captions describe locations as subjectively “cleaner” or “in good condition.”29

Still, the Committee continued to launch expensive advertising campaigns. CCKNYCC used many different ad agencies: after five years with Y&R, the J. Walter Thompson advertising company launched “Cast Your Ballot Here for A Cleaner New York.” Again, the ad agency focused on litter baskets, plastering the image on TV spots, subway platforms, newspaper ads, sides of buildings, and small pamphlets. In 1959, these campaigns spent an estimated $1,368,000. Within the five years running the campaigns, the Committee had commissioned more than five million dollars’ worth of advertising.30

Described to have “done more than any other group to foster the idea that individual ought to be personally responsible for litter,” CCKNYCC certainly made their efforts the most visible.31Their photoshoots, celebrity advertisements, and giant litter basket stunts certainly showed a charismatic side to reducing litter. However, the celebratory self-congratulation by company executives, for company executives, did not give much reason for the internal company policies to rethink their own contribution to waste. “A Cleaner New York is up to You,” the group’s logo emphasized, excluding themselves from the “you.” In creating such a symbol, the group had already done its part.

![]()

The distribution of 1,300,000 leaflets and flyers every year most likely ended up in litter baskets.

The Big City, one of many educational films that were used in schools, were quite different from the five-minute animated films such as “Three Tales of a City” that ad agencies created to show as movie previews, or “Have Litter, Will Travel,” a 15min film that won at the 1962 American Film Festival that makes viewers “pause to think of the tremendous cost the litter-bug imposes on society.”32

♬ Opening Song of the Department of Sanitation educational film, “Take It Away” 1950.